Waste Paper, Bookbinding, and the Literary Imagination in early modern England

in Early Modern England

First (might I chuse) I would be bound to wipe, Where he discharged last his Glister-pipe.

The poet and student of Lincoln’s Inn, Henry Fitzgeffrey, concludes his Satyres and Satyricall Epigrams (1617) with a jesting consideration of the cultural and literary value attached to his printed book. “I woo’d have thee put / Mee in the Folio: or the Quarto cut’”. Fitzgeffrey initially informs his ‘Stationer’, but if this is not possible, suggests that they ‘Rather contrive mee to the Smallest size’,

“Least I bee eaten under Pippin-pyes.

Or in th’ Apothicaryes shop bee seene

To wrap Drugg’s: or to dry Tobacco in.

First (might I chuse) I would be bound to wipe,

Where he discharged last his Glister-pipe.”

These rhyming couplets signify the familiarity of the lifecycle of waste paper to every individual in early modern England, including those within the four Inns of Court.

What is Waste Paper?

From papyri shopping lists used to line sarcophagi in ancient Egypt to classical Roman poets wrapping fish in mediocre verses, the practice of repurposing and recycling handwritten or printed texts in new forms was prolific, dating back thousands of years.

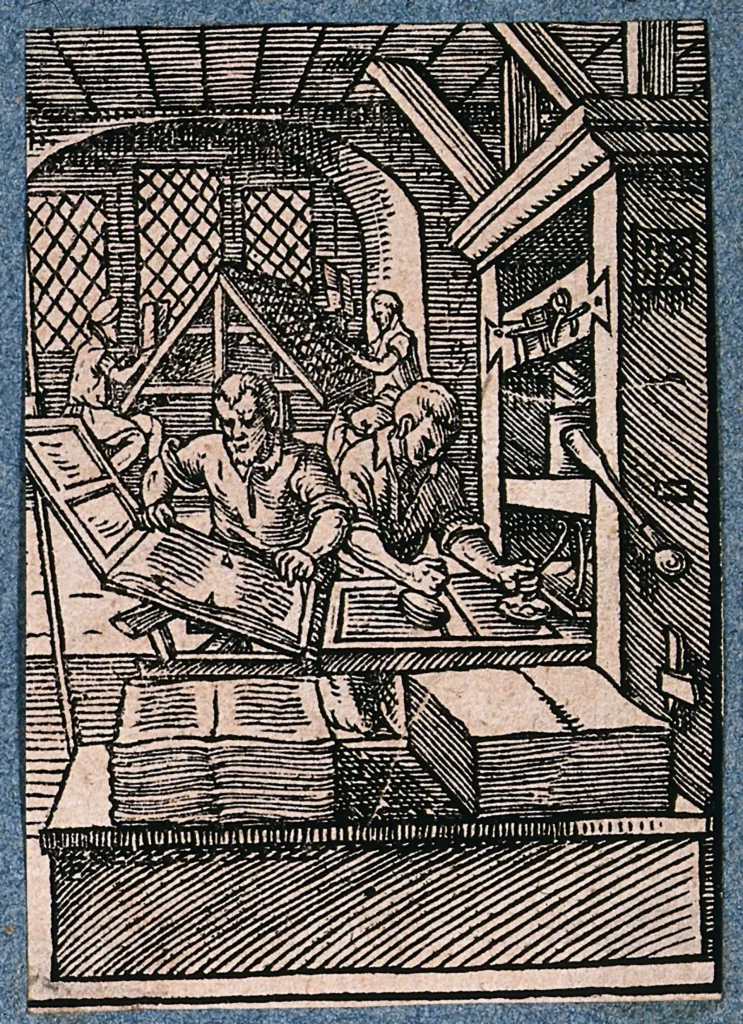

Although the term ‘waste paper’ was first recorded in the mid-late 16th century, the process of (re)assessing, cutting up, remodelling, and then reusing inscribed (and sometimes blank) superfluous paper or parchment was commonplace in both England and the Continent during the Early Modern period. Candidates for recycling included unpopular or excess books, copies containing typos or proof sheets used on the printing press (Figure 1).

Contrary to popular modern thought, the creation and distribution of waste paper during this time was relatively cheap, operating within a developed and distinct paper trade that was well known to the public and bookmakers alike. The waste paper trade benefitted from ad hoc donations (for example, a deceased individual’s library) and organised contributions from titles seized or purchased by the Stationers’ Company. The Company would sell loose fragments of waste to bookbinders, decorators (to make damasked or marbled wallpaper), merchants, and shopkeepers. Although the cost would vary, sale records suggest that a quire (25 sheets) of waste paper typically sold for one quarter of the price of ordinary writing paper, with the Stationers’ Company receiving just over one penny for one in both 1602 and 1621 (around 75 pence in today’s money).

Contrary to popular modern thought, the creation and distribution of waste paper during this time was relatively cheap, operating within a developed and distinct paper trade.

Papery Poetics

From female ‘ragpickers’ who collected used linens from houses and tailors to sell to paper makers, to shopkeepers and merchants who sold their superseded accounts to bookbinders to pulp into pasteboards, early modern people were acutely aware of, and directly involved in maintaining, the lifecycle of paper.

Many authors imaginatively seized upon the different ages of a sheet of paper’s life and the way it could be literally manipulated to make funny, poignant, and didactic arguments. Similarly to Fitzgeffrey’s mocking lamentation on the non-textual uses of his poetry, many authors used waste paper as a literary trope to explore issues of physical and figurative mortality, moral and religious corruption, and the endurance of authorial and political fame and influence. The most prolific author to do this was the poet and playwright Thomas Nashe (1567–1601), who frequently depicted books existing on the threshold of breaking and regeneration. In the introductory address to the readers in his novel The Unfortunate Traveller: or, the Life of Jack Wilton (1594), Nashe informs the reader that Wilton:

“hath bequeathed for waste-paper here amongst you certain pages of his misfortunes. In any case keep them preciously as a privy token of his good will towards you. If there be some better than other, he craves you would honour them in their death so much as to dry and kindle tobacco with them. For a need he permits you to wrap velvet pantofles in them also, so they benot woe-begone at the heels, or weather-beaten, like a black head with grey hairs, or mangy at the toes, like an ape about the mouth. But as you love goodfellowship and ames-ace [a game of dice], rather turn them to stop mustard-pots than the grocers should have one patch of them to wrap mace in: a strong, hot, costly spice it is, which above all things he hates. To any use about meat and drink put them to and spare not, for they cannot do their country better service. Printers are mad whoresons; allow them some of them for napkins.”

Here, Nashe utilises the trope to playfully entreat readers to ‘honour’ the deaths of ‘better’ authors by breaking apart, repurposing their work, and breathing new life into their work in the form protective waterproof “wrap[pers] for velvet pantofles” (slippers), “napkins”, and (with a pun) “privy tokens” or toilet paper.

Despite Nashe’s literary utilisation of the non-textual function of waste paper, a highly symbolic, hopeful use can be found in John Taylor’s encomium to paper, The Praise of the Hemp-seed (1620). In this poem, Taylor applauds the power of printed paper, regardless of whether it remains bound in a book or as a loose waste sheet, to immortalise the words, ideas, and identities of authors, where:

“In paper, many a Poet now survives

Of else their lines had perish’d with their lives,

Old Chaucer, Gower, and Sir Thomas More,

Sir Philip Sidney, who the Lawrell wore,

Spencer, and Shakespeare did in Art xcel,

Sir Edward Dywer, Greene, Nash, Daniell.

Siluester, Beumont, Sir John Harrington,

Forgetfulness their works would overrun,

But that in paper they immortally

Do live in spite of death, and cannot die.”

In this verse, Taylor optimistically imagines that the ‘immortality’ of medieval and early modern writers such as Geoffrey Chaucer, Philip Sidney, and William Shakespeare is permanently woven into the natural material fibres of the paper into which they are inkily pressed, where the original sources of the rags collected (such as from the dresses of “some Countess, or some Queene”) causes them to transform into “tatters allegorical”.

While Nashe and Taylor imagine different outcomes for the survival (or death) of published authorial legacies, both demonstrate a strong, and highly imaginative, familiarity with a material and literary (waste) paper landscape.

Waste Paper in The Inner Temple Library

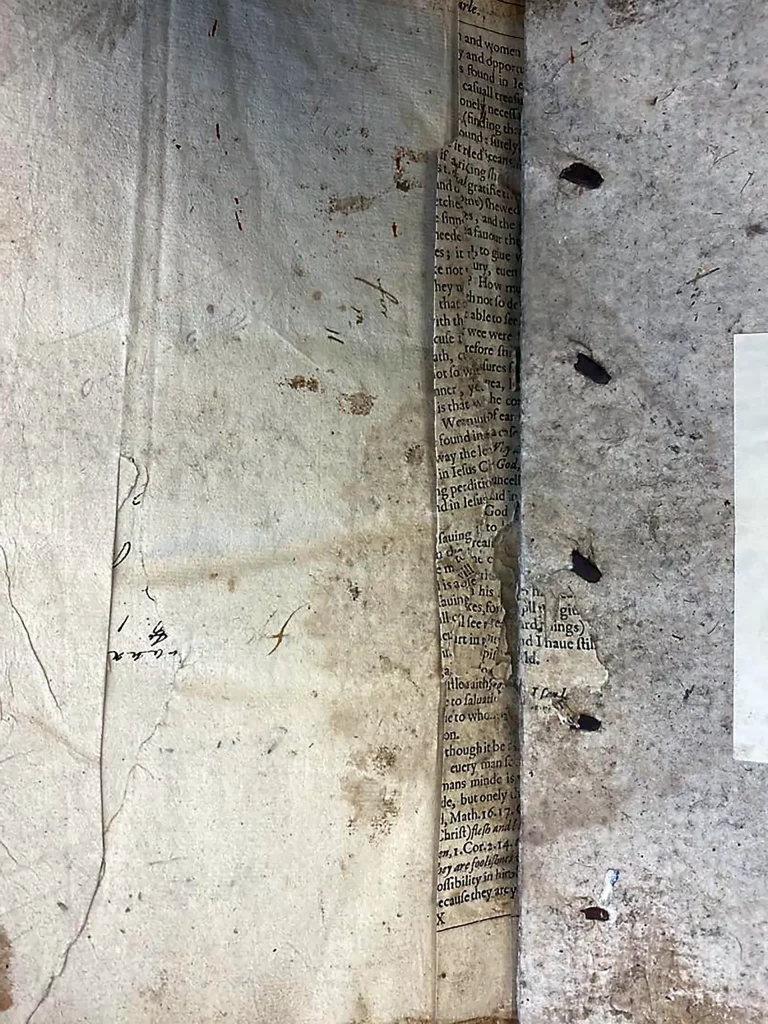

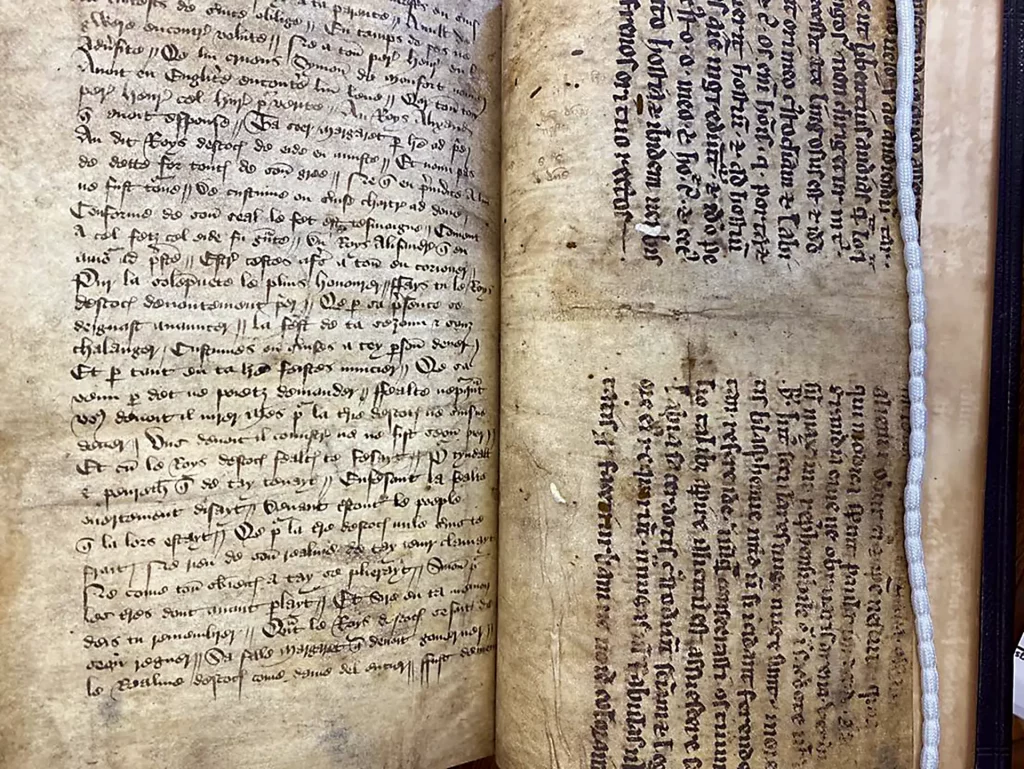

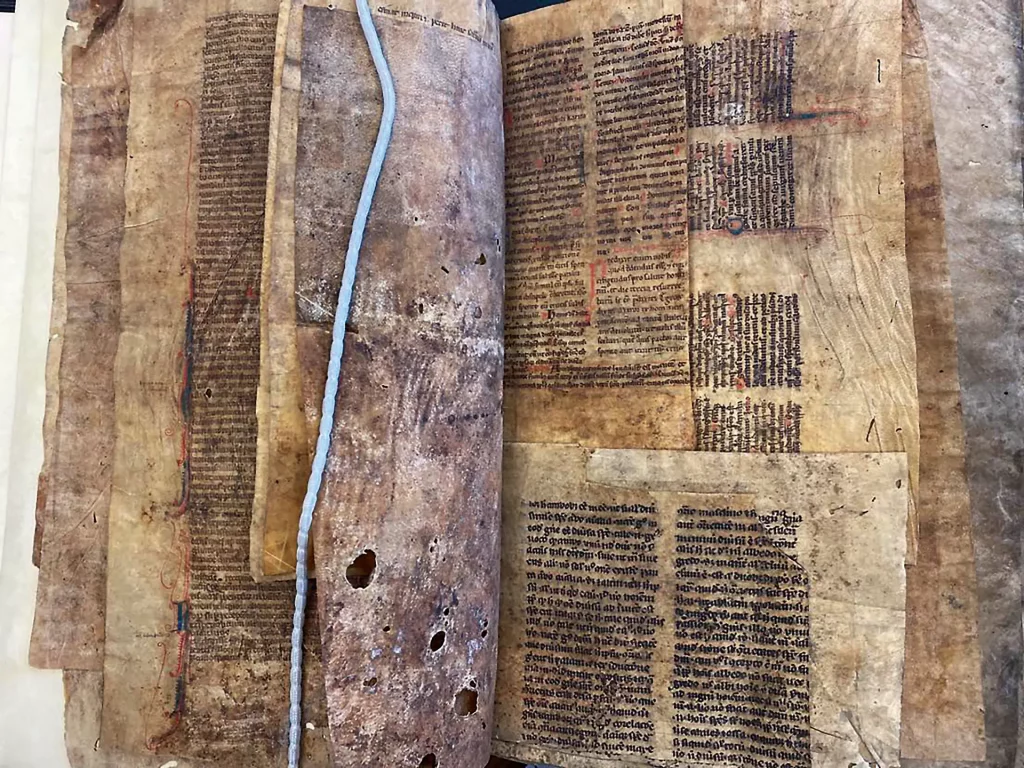

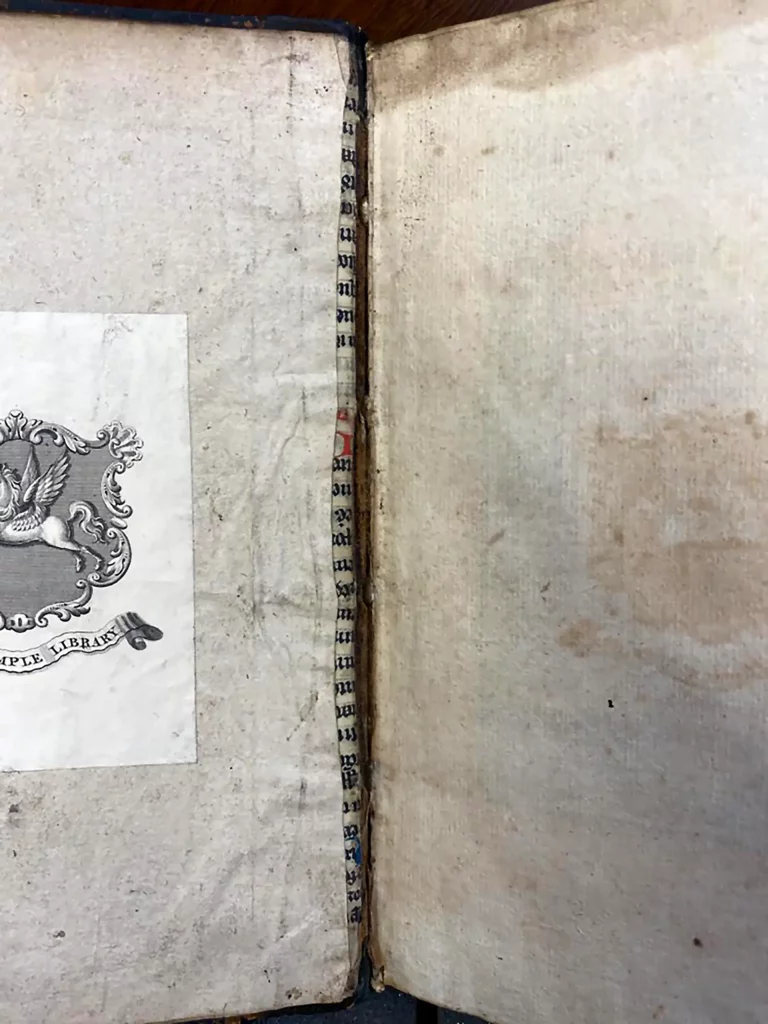

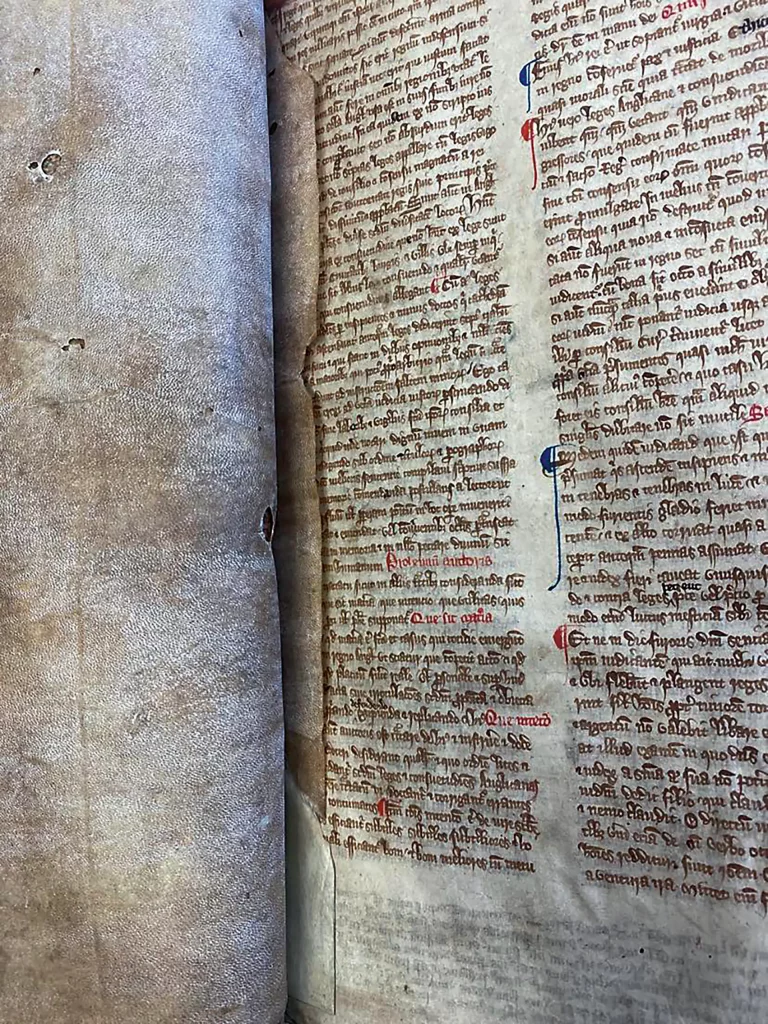

In addition to these uses, the majority of waste paper and parchment was used by bookbinders to assemble and support the main structure of a wide range of book sizes, genres, and types, such as through the use of spine supports, guards (Figure 2), flyleaves (Figure 3), pastedowns (Figure 4), and as limp (flexible) binding covers. Fortunately, there is a wealth of material in the Library’s rare books and manuscripts collection that demonstrates this.

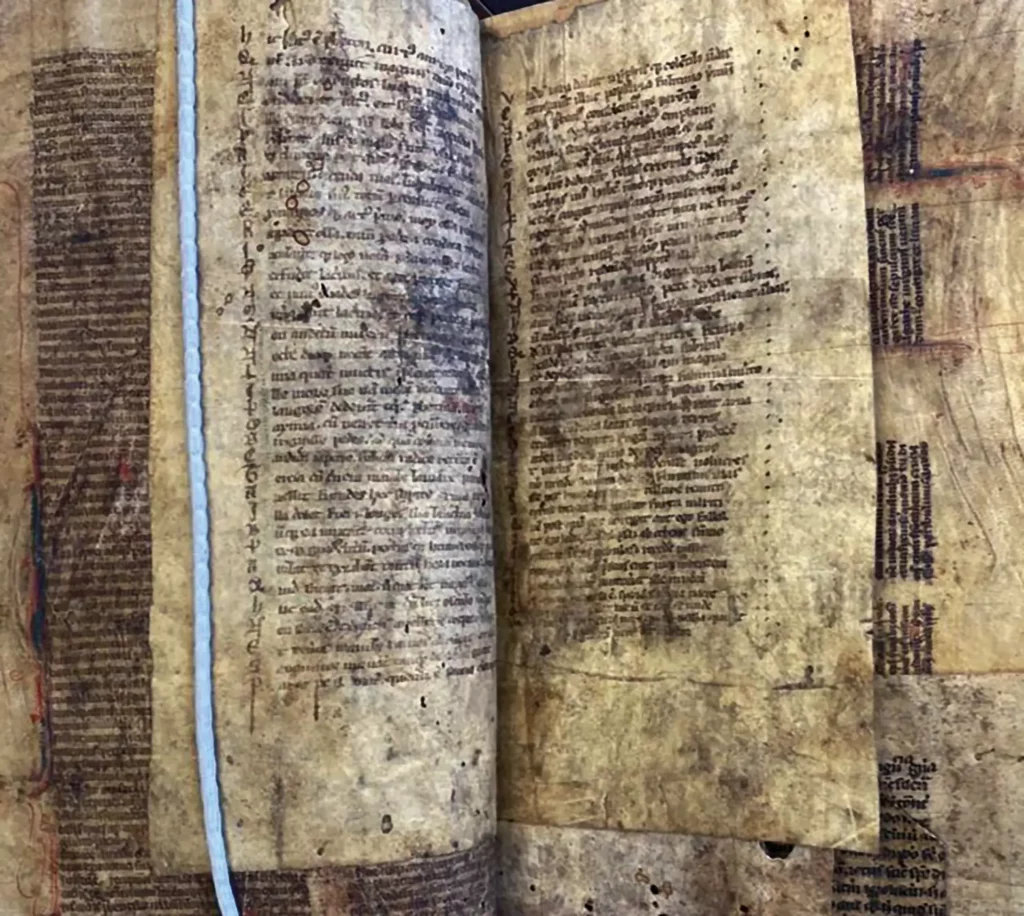

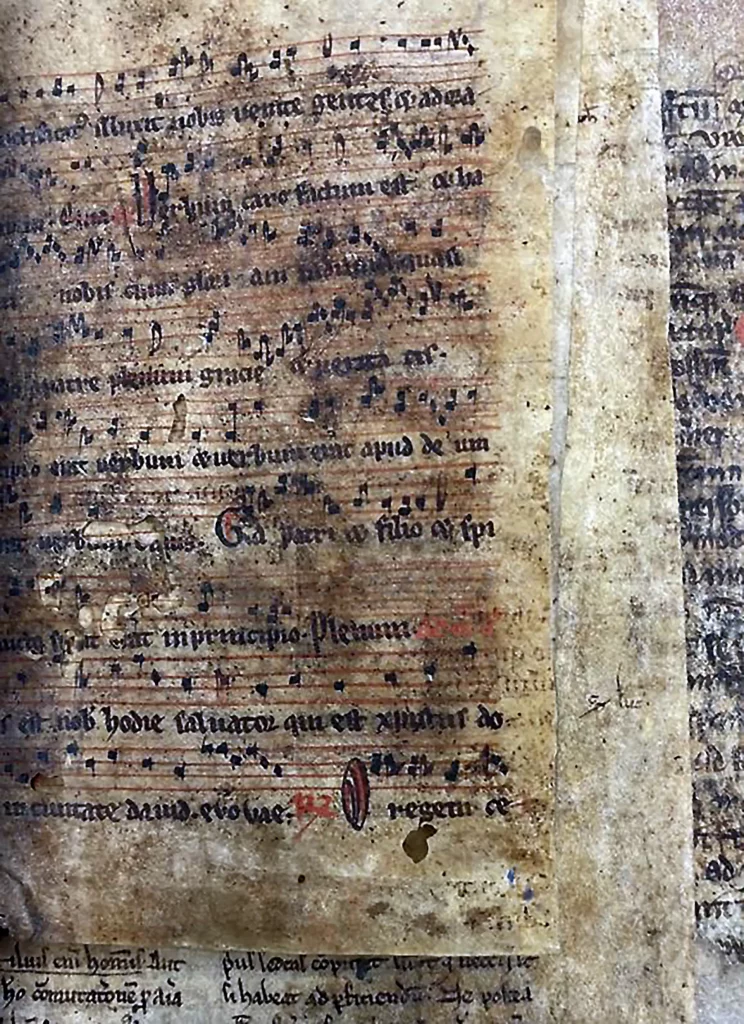

One example of waste in the Inn’s collection is found in the binding of a large, 14th century manuscript copy of English jurist and cleric, Henry de Bracton’s detailed treatise on English jurisprudence, De Legibus Angliae (‘On the Customs and Laws of England’) (Figure 5). This volume, which has had its original spine and boards replaced, contains 39 parchment scraps and sheets from medieval manuscripts of varying types, genres, periods, qualities and sizes, including sheet music (Figure 6), 12th/13th century monastic poetry, and uninscribed vellum (Figure 8), which have been remodelled to support and protect the physical integrity of both the binding and Bracton’s manuscript. The high volume of torn-apart medieval manuscripts in this palimpsest, which feature often in other volumes in the Inn’s collection, is likely the result of the violent seizure, breakage, and dispersal of manuscripts from monastic libraries after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the early-mid 16th century. Significantly, there are a number of annotations present from both the Early Modern and Victorian periods, evidencing readers’ interactions with the snippets.

The high volume of torn-apart medieval manuscripts in this palimpsest, which feature often in other volumes in the Inn’s collection, is likely the result of the violent seizure, breakage, and dispersal of manuscripts from monastic libraries after the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

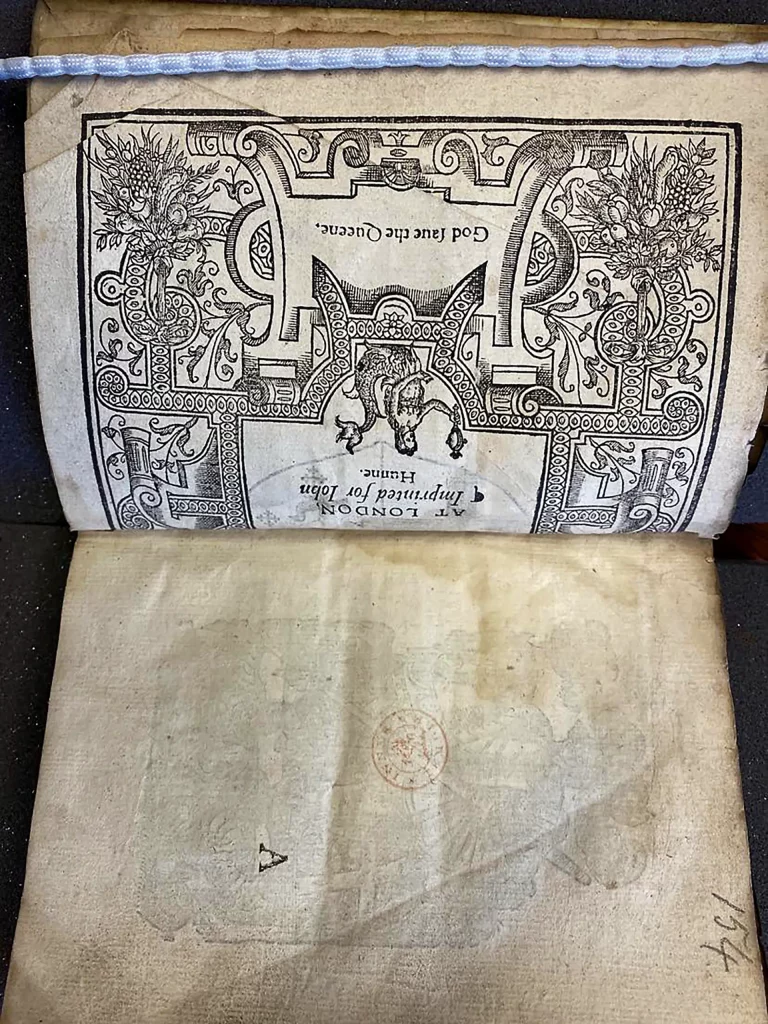

Another exciting instance of waste in our collection is in our copy of the anonymously penned A brief discovery of Doctor Allens seditious drifts, printed by John Wolfe in Distaff Lane near St Paul’s Cathedral in 1588 in its original vellum binding. At the front and back of this small book – the only printed rebuttal of Cardinal William Allen’s (1532–94) published treatise supporting the Spanish Armada’s invasion of England and his case for the assassination of Queen Elizabeth I – are two flyleaves taken from the title page and an extract of the first edition of Raphael Holinshed’s influential Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1577). Printed in London by John Hunne, it was a sweeping narrative of the history, language, and people of England, Scotland, and Ireland from antiquity to the reign of Elizabeth I. The second (larger) edition of 1587 is famously one of the main sources of many of Shakespeare’s histories and tragedies, such as Richard II and Macbeth, and of John Milton’s historical knowledge and political philosophy.

It was a sweeping narrative of the history, language, and people of England, Scotland, and Ireland from antiquity to the reign of Elizabeth I.

While the rotated title page was primarily sewn in to protect and strengthen book’s front pages and spine (Figures 9 and 10), its stark inclusion alongside this specific text highlights not only that extra copies of the first edition were becoming redundant with the publication of the second, censored version, but may also, unintentionally, produce some symbolic significance for an attentive reader examining it. More specifically, enclosing a commentary that simultaneously supports monarchical power and rejects papal influence over religio-political affairs (A brief discovery), with clear portions of text from a popular historical work likely known by readers to be positively biased towards the Tudor dynasty (Chronicles), potentially generates a conversation between the two sources on historical and contemporary realpolitik in Britain, particularly about the influence of the English monarchy (and Elizabeth I) in national and global affairs at a time of great uncertainty. A brief discovery closes with a rallying cry, directly asking its readers to follow both God’s and Elizabeth I’s truth and knowledge to ensure that the “strength of [the] Realme” continues to remain “far greater” than it was in “any Princes age” (p.127) that had come before, periods of time which readers may, through viewing the encapsulating printed waste, remember that the Chronicles traverses and explores in thrilling detail.

Afterlives of Early Modern Waste Paper

So how do we know so much about the material origins and literary reception of waste? Between the late 17th and early 20th centuries, the practice of locating and salvaging waste paper from bookbindings was popular amongst collectors, librarians and antiquarians, often as part of personal projects. Amongst this group of gatherers, which also included the diarist Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) and Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Tenison (1636–1715), was bibliophile (or, some would argue, biblioclast) John Bagford (1650/51–1671) and Dorothy Schullian (1906–89), Curator of Rare Books at the Armed Forces Medical Library (now the National Library of Medicine) in Maryland. Armed with a bookseller supplying him with “waste books … [and the] liberty to take out of them what [he] thought fit”, Bagford set about deconstructing books and giving a second life to waste manuscript fragments and other printed material – such as title pages, frontispieces, and woodcut borders – in the creation of an 800 page record of typographical developments. Unfortunately, Bagford did not complete this bibliographic chronicle. Schullian, on the other hand (and like many other collectors in Oxford and Cambridge college libraries during the 19th and 20th century) “entered a bibliographer’s paradise” in 1953 by soaking and loosening layers of book bindings in water to recover dispersed manuscript and printed waste fragments and restore them back into their original volumes. Schullian’s project, named the Bathtub Collection, reconstituted printed fragments from both well-known classical authors and unfamiliar texts, one of which was used to create uncut sheets of playing cards.

The last decade has seen a shift in attention to and reception of waste, with researchers like Anna Reynolds, Adam Smyth, and Tara Lyons approaching it as something not merely as a forgettable, superficial non-textual material but as pieces of literature that can and should be read to reveal both the lives and imaginative workings of their individual authors and the book tradespeople involved in their creation (and destruction).

Compared with manuscript waste, such as the title page and text from Holinshed’s Chronicles, printed waste has only relatively recently received scholarly attention from book historians, bibliographers, and literary scholars, especially if it remains in situ within early modern bindings. However, the last decade has seen a shift in attention to and reception of waste, with researchers like Anna Reynolds, Adam Smyth, and Tara Lyons approaching it as something not merely as a forgettable, superficial non-textual material but as pieces of literature that can and should be read to reveal both the lives and imaginative workings of their individual authors and the book tradespeople involved in their creation (and destruction). How many more lives and stories is the waste paper in The Inner Temple Library’s early printed books and manuscripts waiting to tell to a reader that wants to listen?

Lily Rowe

Graduate Trainee Librarian