Criminal Law and Mental Health

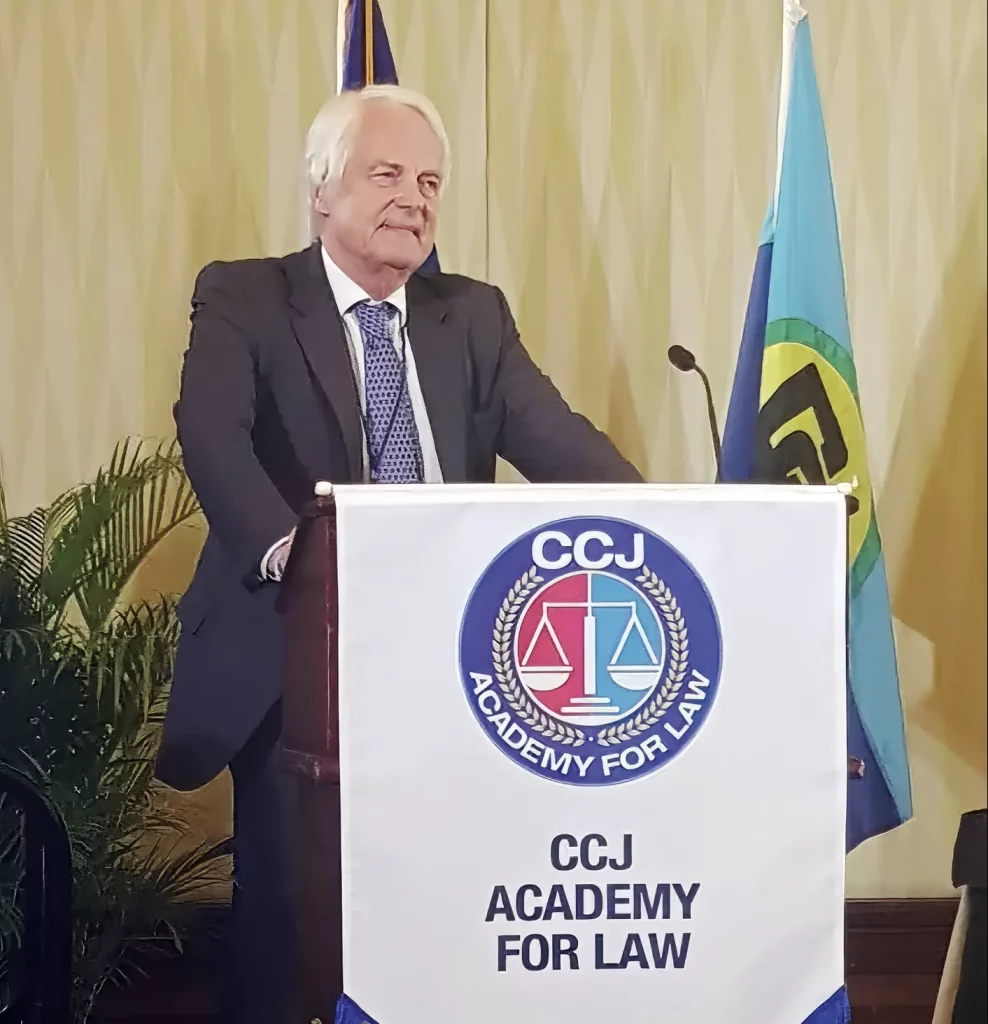

From a lecture delivered to the Caribbean Court of Justice Academy of Law 7th Biennial Conference on “Criminal Justice Reform in the Caribbean: Achieving a Modern Criminal Justice System” on Thursday 19 October 2023, during his visit to the Caribbean as Treasurer.

Introduction

It is a great privilege to be able to address you at this important conference on an issue which underlies so many of the problems facing criminal justice, but in my view receives too little attention. Throughout my career I have specialised in medical law. In that capacity, I have experience of the wider issues of mental health and their interaction with the criminal justice system. I have chaired inquiries and reviews into the failure of mental health services contributing to the death of innocent people at the hands of the mentally unwell. A speaker yesterday mentioned the importance of prevention if we are to tackle the increasing demands on criminal justice, and consideration of mental health is surely a factor in that.

In England and Wales, the law concerning the treatment of serious mental health issues is governed by 40 year-old mental health legislation which deals with compulsory treatment in both the criminal and non-criminal settings. There is room for improvement: the Mental Health Bill has been before Parliament but I have it on good authority that it has been shelved until after the general election.* What follows is my personal view and not those of The Inner Temple and of our members.

Before describing the system as it is today, let me share a story which highlights what can go wrong when serious mental health issues are not dealt with holistically and with a view to reducing risks for the patient and the public before the intervention of criminal justice is needed.

Mr Butler was a 48 year-old single man living on his own in a council provided apartment in Birmingham. He was a paranoid schizophrenic, but had no history of violence. He had been treated intermittently in hospital, both voluntarily and compulsorily, the last time in 2001. When he was discharged he was given the flat to live in and received medical and social service support – or at least should have been. After the events I am about the describe, over 430 doses of his prescribed medication were found it the flat – making it clear he had not been taking this and that no one had noticed. He began to get into financial trouble and was not claiming benefits to which he was entitled, falling into arrears with his rent, and being threatened with eviction by the housing authority. His behaviour was noticed to be odd by a neighbour. He was visited by a social worker and a psychiatrist who observed a large knife on the sofa and damage to a door – his explanation that he was practising martial arts, something he had not shown any previous interest in, was accepted. The housing authority did not know he was under psychiatric treatment, and neither social services nor the psychiatric team knew he was in financial difficulty or had trouble with the neighbours. On 21 May 2004, two things happened, one after the other: a man from the housing authority served a notice of eviction on him; and an employee turned up to mend the garden gate on the path which led to his front door. On seeing this, Mr Butler issued from his front door brandishing the knife, and understandably and wisely the handyman fled, reporting the incident to his employer who, in turn, reported this to the police. Equally wisely, the police asked the medical services whether there was any psychiatric history, to which a negative answer was given (wrongly) owing to the records not being available to the person called. So the police turned up in numbers to arrest Mr Butler. Tragically he saw them before they could arrest him and he fled, upon which a chase occurred involving dogs, police, sirens, and a helicopter – doubtless terrifying Mr Butler and reinforcing his paranoia. He was eventually confronted by an unarmed plain clothes officer, DC Swindells, who bravely (but in ignorance of any of the background I have described) attempted on his own to detain and disarm Mr Butler, who with one stab killed him. Mr Butler was convicted of manslaughter through diminished responsibility and sent to hospital, and the officer’s family and police force lost a much-loved husband, father and respected officer. All of which, I thought, could at least possibly have been avoided if the various agencies responsible for care and oversight had coordinated their information and strategies. I chaired a panel which reviewed the case and our report is in the public domain.

I tell this story to demonstrate an obvious fact, which is that serious crime committed by the mentally unwell can only be prevented by co-ordinated action of many agencies who are trained to see issues, where relevant, as having a mental health element.

I ask you to hold that story in mind while I offer you a little of the context in which mental health care in England and Wales is available to those in need of it, and how our criminal justice system takes into account the mental health of accused and convicted offenders.

Context

Unfortunately, the current system is neither effective nor capable of addressing the issues for society arising from mental illness. There are a number of points of concern.

- Demand: there was a 40 per cent increase in detentions under the existing mental health legislation between 2007 and 2016. It is increasingly open to question whether there is the capacity to address either the needs of the detainees or those of society generally to protect them or the community from the risk they represent.

- Discrimination: a disproportionate number of people from ethnic minority groups are detained under the mental health legislation.

- Not up to date: the processes required under the legislation are inconsistent with modern learning about mental health treatment and care.

- The tip of the iceberg: those subject to treatment orders under the Mental Health Act are only a small proportion of those with such issues who have been given some form of custodial sentence.

- Capacity: our prison estate is currently full, to the extent that judges are reportedly being advised to defer passing sentences of imprisonment where possible. On 12 October 2023, it was reported that there were 88,016 people in prison against a capacity of 88,667, and the government is reported to be taking emergency action to increase the number of places. It is likely that a large number of inmates have mental health problems. A report to Parliament by its Public Accounts Committee stated that in 2016–17, up to 90 per cent of prisoners had mental health issues, although the data kept might not have been reliable or up to date. There were 120 self-inflicted deaths and 40,161 incidents of self-harm reported. 70 per cent of the suicides involved prisoners known to have a mental health condition. The same report stated that it was a “disgrace” that too many prisoners waited “far too long” to be transferred to hospital or secure units for acute mental health problems. In 2016–17 two-thirds of prisoners eligible for transfer to hospital waited longer than the legal limit, with some waiting for over a year. A later report by the House of Commons Justice Committee, unsurprisingly, found that the provision of mental healthcare was inadequate. It is highly unlikely that the situation has improved since then.

Prisoners do not lose their human right to receive proper care and treatment. The WHO has stated that:

- “The state has a special duty of care for those in places of detention which should cover safety, basic needs and recognition of human rights, including the right to health.”

- “Enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health is a fundamental human right. Prisoners should therefore have the same standard of medical care as people living in the community.”

The United Nations has long agreed standard minimum rules for the medical and mental health treatment of prisoners. The Nelson Mandela Rules approved by the General Assembly provide that:

- “The provision of health care for prisoners is a State responsibility. Prisoners should enjoy the same standards of health care that are available in the community … without discrimination on the grounds of their legal status.”

The Mental Health Act

The Mental Health Act 1983 (“the 1983 Act”) contains the statutory provisions for the compulsory mental health treatment, whether through a sentence of the court or simply for patients needing treatment. The principle is that regardless of the route by which a person comes to treatment, this is not a punishment but treatment of a diagnosed condition, dealing first with resources available in the criminal justice system.

Preliminary medical reports

In any case where an offender is to be sentenced and appears to be suffering from a mental disorder, the court must generally obtain a medical report. Further, where a sentence of imprisonment is made, all medical reports and information possessed by the court should be passed to the prison authorities.

Culpability

In considering the appropriate sentence, the court first has to consider the extent to which culpability is affected by a mental disorder. Whether or not the disorder influences culpability is relevant to the type of sentence the court may pass and the degree of danger presented by the offender.

Choice of type of sentence

The court can hand down the following sentences:

- Fine/discharge (where no therapeutic intervention is required and/or the offence is minor)

- Community Order (where the offence is imprisonable) – if treatment/support is required, the following requirements/conditions can be made:

- Mental Health Requirement (this may be made by magistrates or judges sitting in the Crown Court)

- Rehabilitation Requirement

- Alcohol Treatment Requirement

- Drug Rehabilitation Requirement

- Prison – even if custody is inevitable, a mental disorder may make a custodial sentence disproportionate or indicate a shorter term than might otherwise be the case.

- Mental health disposals: With all forms of mental health disposal, the court must be satisfied that the relevant treatment is available. This can be outside the NHS or a local authority, but particular care is needed to ensure availability, suitability, and sustainability. This can be a considerable challenge and can delay disposal of cases. The following disposal orders are available:

- Hospital order – detention in hospital for treatment (The 1983 Act, section 37).

- This may be made by a magistrates or Crown Court on evidence of two doctors regarding mental disorder and availability of treatment, and satisfied that place and treatment is available.

- Note that only ‘mental disorders’ as defined give the courts power to make an order. Thus, paranoid schizophrenia is a mental disorder but believing in ordinary conspiracy theories, for example, is not.

- Detention is initially for six months but may be extended; discharge can be made by a hospital manager, responsible clinician or nearest relative. Cases are referred to a Mental Health Tribunal either by application or by the manager after six months, and also after three years since last considered.

- Restriction order – indefinite detention in hospital where necessary for protection of the public from serious harm. Release can be made by the Secretary or State or, sometimes, a Mental Health Tribunal (The 1983 Act, section 41). When deciding whether to add section 41 restrictions, the Crown Court must consider:

- the seriousness of the offence committed;

- any previous offences the accused may have committed; and

- the risk of committing more offences in the future.

- Guardianship order – the offender is placed under the guardianship of a local authority or approved person usually in the community (The 1983 Act, section 37). This may be made by magistrates or judges sitting in the Crown Court.

- Prison sentence with hospital and limitation direction – detention in hospital for treatment, followed by a transfer to prison to complete their sentence when well enough to do so. This may only be made in the Crown Court and when the defendant is 21 or over. The court must consider whether criteria are met for a hospital order alone (The 1983 Act, section 45A).

- Hospital order – detention in hospital for treatment (The 1983 Act, section 37).

Care of charged persons pending trial

Similar steps can be taken to protect charged persons and the public pending trial:

- Remand to hospital for treatment pending trial – this can be imposed for up to 28 days (extendable by the court) (The 1983 Act, section 36).

- Remand to hospital for reports on the accused’s medical condition (The 1983 Act, section 35).

Care of mentally ill patients other than under the criminal justice system (briefly)

While most mentally ill patients receive treatment on a voluntary basis either in the community or in hospital provided by the NHS, some care can also be provided by private providers, which can be very expensive. Where treatment is or may be necessary on a compulsory basis, the 1983 Act provides two types of order enabling it: a section 2 order for assessment, and a section 3 order for admission for treatment. With the exception of the provisions for restricting the discharge of a convicted offender under section 41, the rules regarding treatment and discharge are much the same under the criminal and the civil regimes.

The role of the Mental Health Tribunal

The role of the Mental Health Tribunal is to review the detention of patients who are subject to orders made under the 1983 Act, and, where required, it may discharge or alter the terms of the original order. Most patients reviewed are detained in hospital outside the criminal justice system, but the tribunal also hears cases where patients are living in the community under restrictions placed on them under the 1983 Act – for example, patients subject to Community Treatment Orders.

The Tribunal panel comprises a Judge, a medical member (a Consultant Psychiatrist) and a specialist member who has experience around mental health in relation to social needs. They receive reports from qualified experts and the responsible clinician and a member of the nursing team.

Other safeguards

All detention is open to abuse. There are a number of safeguards:

- A code of practice to be followed by hospitals, doctors et cetera;

- A complaints process is available for patients and relatives;

- A regulator – the Care Quality Commission (previously the Mental Health Commission) – oversees the system through inspections and monitoring of certain types of treatment and publishes reports of inspections and a rating. Bad ratings can result in special measures.

The future

The Government has published a draft Bill amending the 1983 Act, but it does not seem that it will be presented during this Parliament, much to the annoyance of the author of the report on which the proposed amendments are based, Sir Simon Wessely. He proposed, and in its response the Government accepted, that four fundamental principles should underpin the law in this area:

- Choice and autonomy – ensuring service users’ views and choices are respected.

- Least restriction – ensuring the 1983 Act’s powers are used in the least restrictive way.

- Therapeutic benefit – ensuring patients are supported to get better, so they can be discharged from orders made under the 1983 Act.

- The person as an individual – ensuring patients are viewed and treated as rounded individuals.

With regard to the mentally ill offenders, the report recommended:

- Police cells should no longer be used as a place of safety, but purpose-built health-based facilities should be provided;

- All criminal courts, including magistrates, should have the power to send people immediately to hospital for assessment and treatment subject to bed availability, and should no longer have the power to remand a defendant to prison for their own protection and welfare on mental health grounds;

- The excessive remand of the mentally ill to prison rather than hospital needs to be addressed urgently;

- There should be shorter time limits for transferring mentally ill prisoners to hospital. It should be possible for a clinician to grant leave or transfer of restricted patients where they do not pose a serious risk to themselves or others;

- The Mental Health Tribunal should be given power to order the transfer of a restricted patient from one hospital to another and to grant leave or discharge, including discharge with conditions; and

- There should be one recognised method of assessing a defendant’s level of risk shared by all required to do so, including the psychiatrist reporting to the court, the judge, the Tribunal and the Ministry of Justice.

In conclusion, the law is far from perfect. Should autistic people or people with learning difficulties be included? There is controversy because there should be (so say some in this world) a system of reviewing the lawfulness of detention periodically.

Another matter giving great concern is that ethnic minority citizens are over-represented, and this should be addressed.

However, there is at least a system which seeks to offer the same mental health facilities to those convicted of crime as to those who are not. Particularly if the recommendations are followed and properly resourced, it does offer some hope of reducing the amount of criminality and harm to the community as opposed to through deterrent type punishment.

*In the King’s Speech delivered on 17 July 2024, the Labour government committed to modernising the Mental Health Act by passing a Mental Health Bill.

Sir Robert Francis KC

Treasurer 2023

Serjeants’ Inn Chambers (Associate Member)