An Archaeological Journey Through Time: The Landscape of Inner Temple

In the heart of London, beneath the bustling streets and modern buildings, lies a rich tapestry of history waiting to be discovered. The archaeological searches between 1997 and 2023 at The Inner Temple were prompted by necessary planning approvals for new construction. They offer a fascinating glimpse into the city’s historical evolution, revealing treasures from every period of our country’s history.

British architect Ptolemy Dean, who designed our Millennium column in Church Court, aptly describes the searches as a “privileged glimpse” of what lies quietly beneath our feet in modern-day London.

Ancient Land

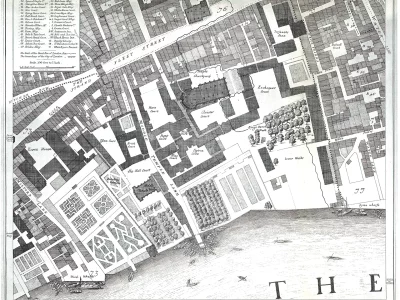

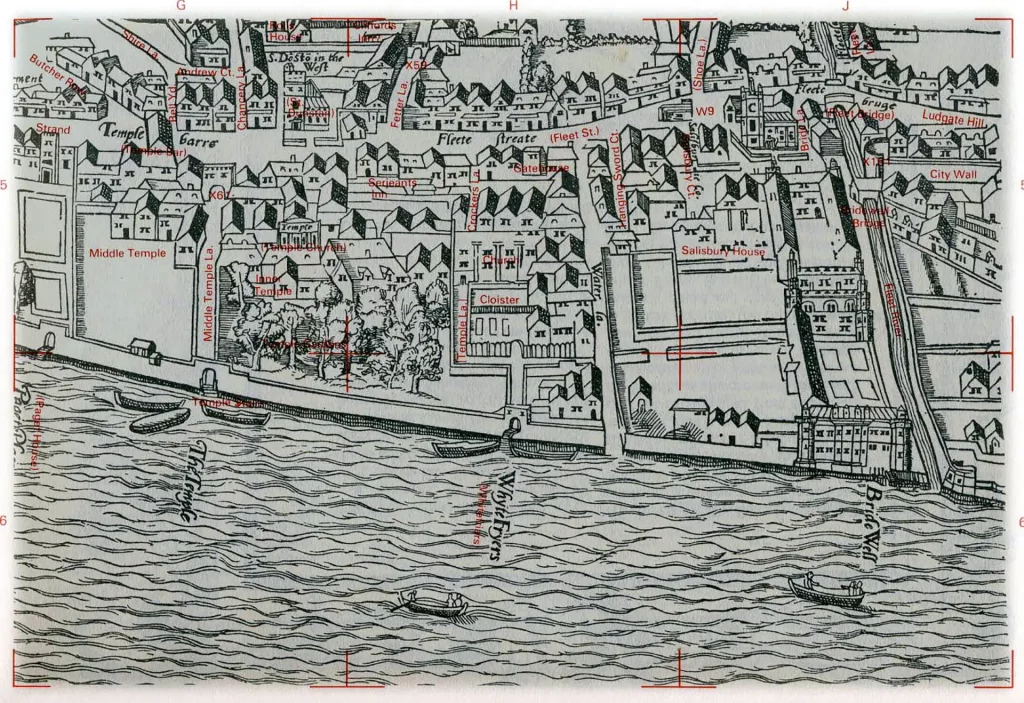

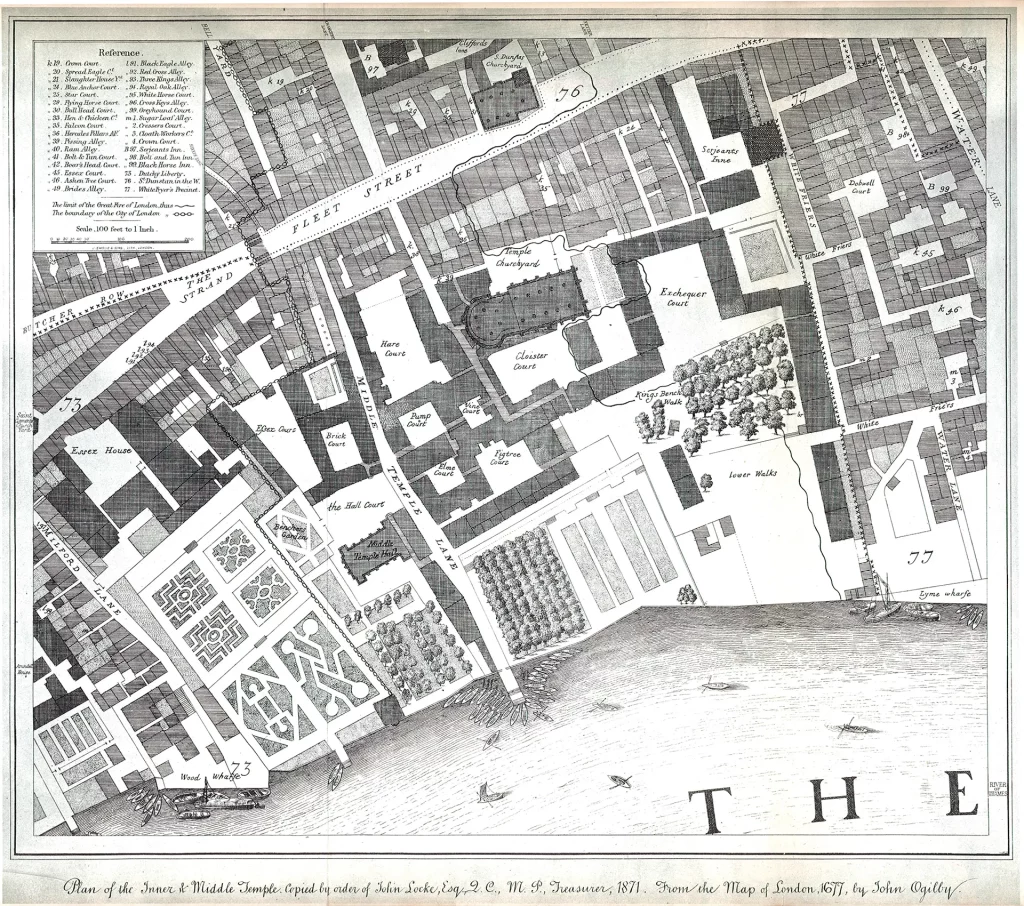

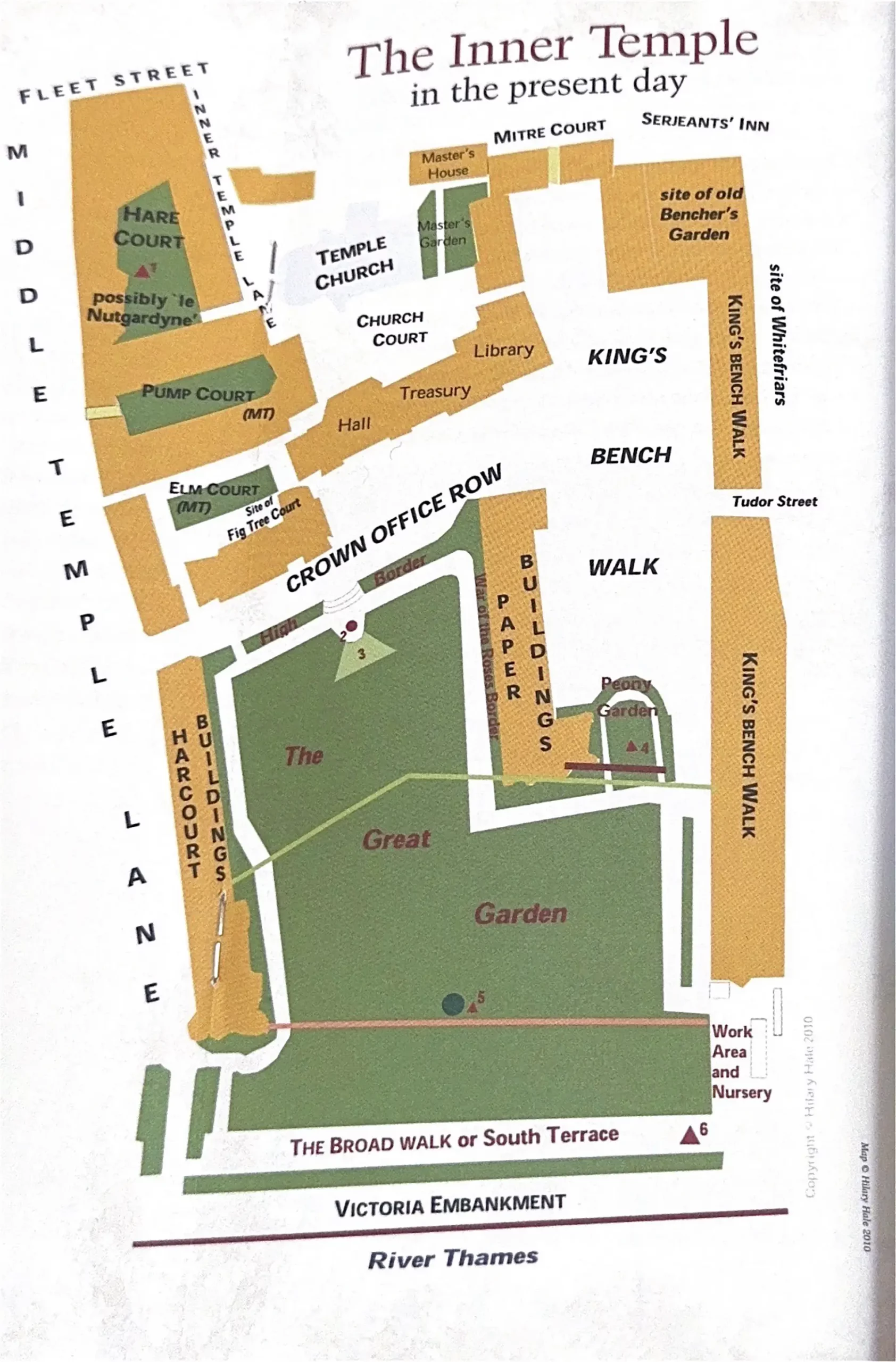

Exploring the deeper sedimentary levels of The Inner Temple is crucial for understanding its archaeological timeline. Originally, the topography featured a natural incline descending from Fleet Street in the north towards the Thames in the south. Over the centuries, this area has been terraced significantly, resulting in a pronounced slope that ends at the Victoria Embankment. Historically, the medieval waterfront lay approximately 40 metres south of the Treasury Building, and it is believed that the waterfront during the Middle Saxon period was situated just behind this medieval boundary.

A map of the Inn shows the original line of the Thames in the Saxon period. This was extended three times from the 16th century until the 19th century, pushing the Thames further away and providing the Temple with more land and garden.

Present-day structures are partially integrated into this slope, with the ground level in Church Court notably elevated. Soil composition studies have revealed remarkable signs of early human habitation. The earliest layer, dating back circa 56 million years, to the Paleogene period, was discovered in the Treasury Building’s lift pit, consisting of coarse natural gravel. This gravel is part of the site’s drift geology, the transportation of sediment which over time forms landscape, overlaying the bedrock of the London Clay Formation. This gravel layer was covered by ‘clayey silt’ (formed of silt and clay) from the Late Pleistocene to Early Holocene periods, circa 11,700 years ago, indicating the site was dry land suitable for habitation during that time.

Prehistoric Occupation: Mesolithic and Neolithic Periods

Archaeological evidence suggests intermittent human activity in central London during the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods (12,000–4,000 BC). Flint materials discovered at The Inner Temple, particularly those from the Thames, point to this era of prehistoric occupation. A modest collection of residual flint blades and narrow flakes from these periods was unearthed at Church Court and 2–3 Hare Court, and a Mesolithic flint axe was recovered from the River Fleet. While prehistoric artefacts are infrequently found in the immediate area, these discoveries provide valuable insights into early human activity in the region.

Iron Age Burial: A Glimpse into Pagan Practices

A significant discovery at the site includes a skeleton, possibly dating back to the Iron Age (1,200–600 BC). The exact date remains uncertain, but the grave’s alignment and the presence of an iron object, likely a sword or spear, along with a copper alloy item, suggest a potential pagan burial.

Roman Legacy: Londinium’s Western Fringe

During the Roman era (AD 43–410) the Inner Temple site lay outside the Roman city of Londinium, and the Strand is believed to have replaced a Roman road that extended westward from Ludgate along the approximate route of Fleet Street.

Remains from three Roman burials were discovered behind 4 King’s Bench Walk and human remains dating back to the Roman period were also found in Church Court (1999) and Hare Court (1999). Evidence of Roman burials has been found at nearby locations, including Shoe Lane and St Bride’s Church. At St Bride’s, a building with a tessellated pavement was initially interpreted as a mausoleum but later reinterpreted as part of a Roman cellared building.

Saxon Era: From Cemeteries to Settlements

The Temple area lies outside the Saxon settlement of Lundenwic, which was centred on the Covent Garden and Strand area. Excavations at Church Court and Hare Court have revealed significant discoveries from the Middle Saxon era (AD 650–850) to the post-medieval period (AD 1500). These sites yielded stone traces from the prehistoric to the Roman eras, suggesting continuous activity.

Various Saxon discoveries have been made within the Inn’s estate. A sequence of medieval domestic Rubbish Pits dating from the early 11th century were discovered at 5 King’s Bench Walk and a Saxon burial was discovered in Hare Court. Additionally, a Saxon well was found, containing a variety of objects, including bone pins, copper alloy pins and pottery.

Notably, the discovery of Saxon burials, including an inhumation with grave goods, provides valuable insights into Middle Saxon funerary practices in Lundenwic. The finds suggest a high-status occupation site, possibly indicating an important settlement area between Lundenwic and the speculated religious enclave at St Paul’s.

Viking Raid: A Hoard of Saxon Coins

One of the most intriguing finds at Hare Court was a hoard of over 250 Saxon coins dating to AD 841–842. These coins, now housed in the British Museum, were likely buried in response to a Viking raid. The coins came from various moneyers in the Midlands, Kent, Canterbury, East Anglia, and Wessex. This hoard provides a tangible connection to the Viking raids that plagued the region, including a documented raid on London in AD 842.

Medieval Discoveries: The Knights Templar and Beyond

In 1161, the land between Fleet Street and the Thames was acquired by the Knights Templar. They had previously built a round church in the first half of the 12th century in what is now Southampton Buildings off High Holborn. The church at the ‘New Temple’ was consecrated in 1185. In 1307, members of the Knights Templar were accused and charged with heresy. The order of the Knights Templar was suppressed by Pope Clement V in 1308 and the crown ordered an inventory of the Knights possessions in the New Temple. During the reign of Edward III, the Knights Hospitallers, or the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, were eventually granted the land of the Temple. They leased this land to students of the common laws of England, who have continued occupying the site to this very day.

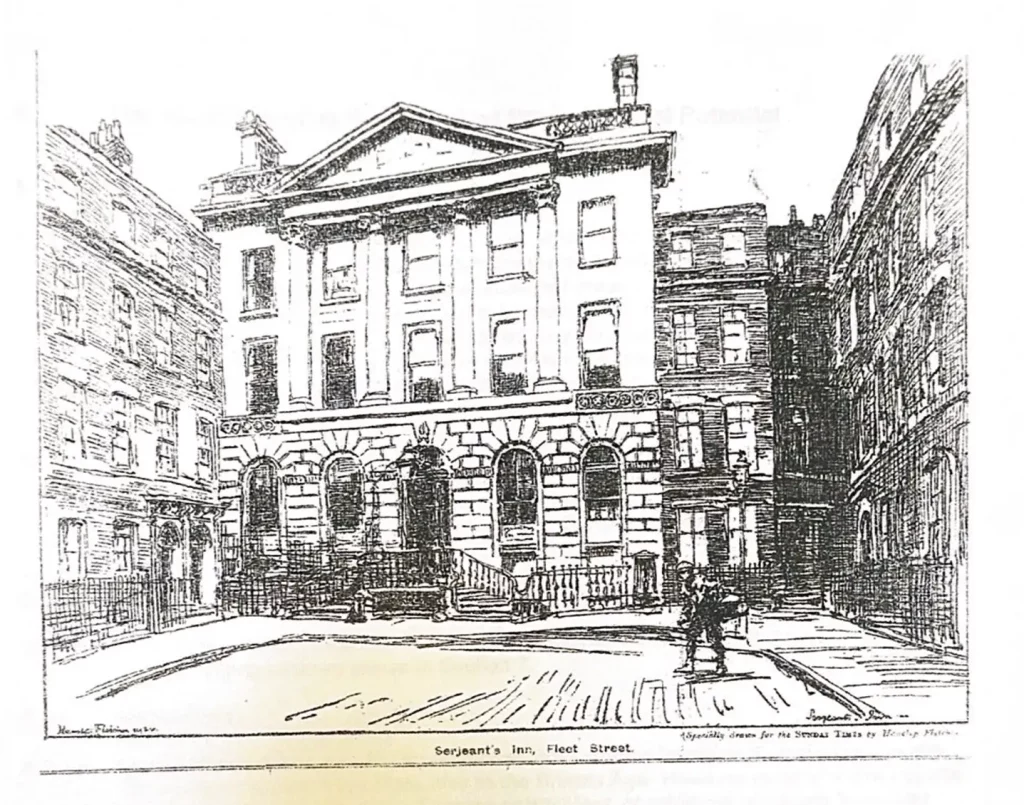

Medieval archaeological remains have been found at a number of sites at the Temple. At 4 King’s Bench Walk, a tile kiln estimated to have out gone out of use between AD 1210–80 was unearthed. In 1878, building work at Child’s Place and 1–2 Fleet Street uncovered the remains of an undercroft with a large central pier, four arches made of greensand (a type of sandstone) and a floor lined with green and yellow glazed tiles. It is suggested that this was a building contemporary with the church, destroyed by Wat Tyler’s rebels during the Peasant’s Revolt in 1381. Several skeletons in five regular rows were found under the last house on the west side of the Middle Temple Lane, again dating back to the period of the Knights Templar.

Excavations in Hare Court have revealed a 12th century quarry pit and garden soil, suggesting that it was used as a garden until the 16th century.

Post-Medieval

In 1540, Henry VIII suppressed the Hospitallers in England during the dissolution of the monasteries, under the 1534 Act of Supremacy. The monarch disbanded Catholic monasteries in England. The Temple site was seized, church assets were disposed, and the policy sought to materially benefit the Crown. However, it continued to be leased to lawyers. Puritan lawyers removed all traces of Catholicism from the church by whitewashing the ceilings and columns. They also covered the tessellated pavement with manure before laying gravestones over the top to create a new floor, two feet above the original. In 1608, James I granted the freehold of the site to the Benchers of The Inner and Middle Temple.

The archaeological search of The Inner Temple has uncovered a wealth of historical artefacts and structures, shedding light on London’s rich and diverse past. From prehistoric flint tools and Iron Age burials to Roman remains, Saxon cemeteries, and Viking treasures, each discovery adds a layer to the complex history of this iconic site.

In 1666, the Great Fire of London destroyed much of the eastern part of the Inner Temple but stopped at the Temple Church and Church Court. Completely unprepared in battling with a fire of such magnitude, it was down to the people of the Inn to save its remains. The Duke of York offered his assistance alongside soldiers, sailors and four engineers, personally directing the operations. Middle Temple was left largely unscathed, save for the loss of the Lamb Building. However, large parts of Middle Temple would be affected by the Temple Fire of 1679 which broke out in Pump Court and spread to New Court.

Excavations around Church Court, Hare Court and the south side of the Temple Church have uncovered a large quantity of green-glazed Border ware pottery vessels and several 17th century skeletons of young people. Examination of their teeth revealed an unusually high incidence of decay, demonstrating a rich diet with large quantities of alcohol. Clothes and personal items were also discovered, indicating the wealth and high status of the Inn’s inhabitants.

Wartime Impact: The 20th Century

The Treasury Building suffered severe damage during the bombings of World War II and was reconstructed in the 1950s.

The Lamb Building’s basement, home to fire debris from the Blitz, highlights the site’s enduring archaeological significance. For example, remnants of the Temple Church’s former splendour were evidenced by decorated floor tiles and Purbeck marble fragments, which were discarded during the 1950s restoration efforts.

remnants of the Temple Church’s former splendour were evidenced by decorated floor tiles and Purbeck marble fragments.

A Rich Historical Legacy

The archaeological search of The Inner Temple has uncovered a wealth of historical artefacts and structures, shedding light on London’s rich and diverse past. From prehistoric flint tools and Iron Age burials to Roman remains, Saxon cemeteries, and Viking treasures, each discovery adds a layer to the complex history of this iconic site. The Inner Temple stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of London’s historical evolution, offering a fascinating journey through time beneath the modern cityscape.

Maryam Khan

Archives Researcher