1500–2023: Snapshots of the Inner Temple Library

This is a truncated version of a talk delivered on 18 March 2024.

When we (the then Master of the Library, and the then newly appointed Head Librarian) first met, we identified in each other a common satisfaction in looking at the lists of names of those who had held our respective posts and knowing that we walked in their footsteps. It is those names that have made the Library. The fabric has changed over the centuries, but our predecessors have forged a consistent chain throughout.

Times change, but the principles remain; the Library was, and is, here to provide members of the Inn, from judges to students, with the materials by which they can research and learn and feed their minds and souls.

The first record of the Library is in 1506. For the first hundred years, the cupboards of books shared the space with the overflow of diners from Hall. By 1606, the Benchers began to frown upon this; the Library, they said, should be “kept sweet and cleanly for the exercise of learning and receiving noble personages”. By 1607, we had spread into another room. In 1608, Sir Edward Coke donated his reports (our first recorded donation) and from then on, the Library grew in size and status. That is until Sunday 2 September 1666, when the Great Fire broke out and the Library was destroyed. It was rebuilt by 1668; bigger and better.

Eleven years later in 1679, fire broke out in the Middle Temple. The spread was prevented by emptying The Inner Temple Library and blowing up most of it with gunpowder. It was rebuilt in a year, but it was still a place of gambling and wine and suppers, as well as books. No catalogue, no Library Keeper, no rules.

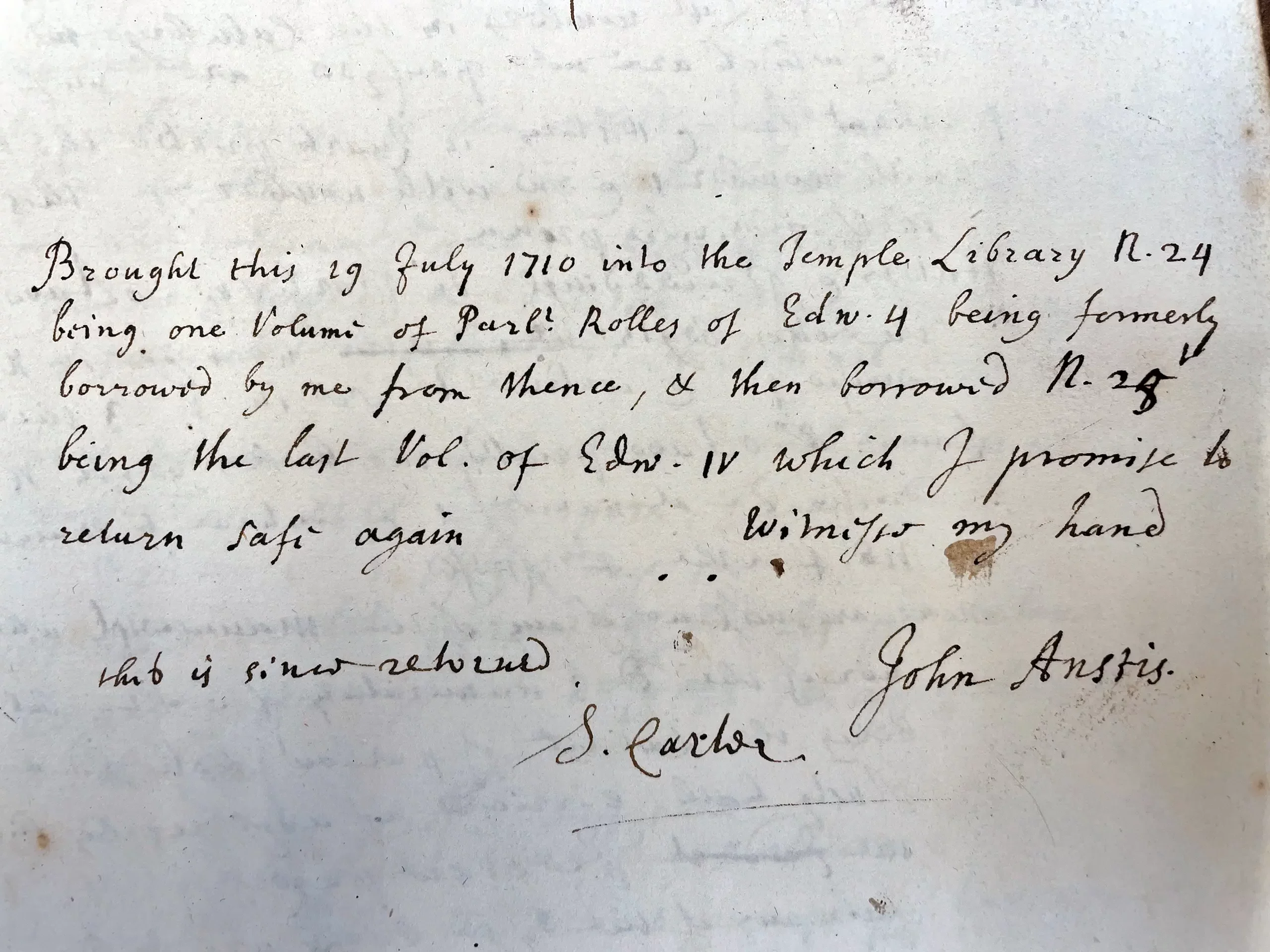

Then, in 1707, William Petyt, the Treasurer, who had been Keeper of the Records at the Tower of London, offered his extraordinary collection of manuscripts. A new library was built to house them in 1709, the same year the first Librarian, Samuel Carter, was appointed. Admitted in 1665, and called to the Bar in 1673, Carter received an annual salary of £20. An apparently “aged and impecunious barrister” and a seemingly inaccurate law reporter, Carter is more favourably remembered as the first to work on William Petyt’s collections. By 1713, he had produced the earliest catalogue of the Library. It identifies theological, historical, and philosophical collections. For ‘law books’, Carter reserved special treatment announcing that he had “made an alphabet”. Although Carter was not regarded as a trailblazer in his legal endeavours, librarianship at The Inner Temple had begun. Carter remains the only Inner Temple Librarian with an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography. He was buried on 8 March 1713 in Temple Church.

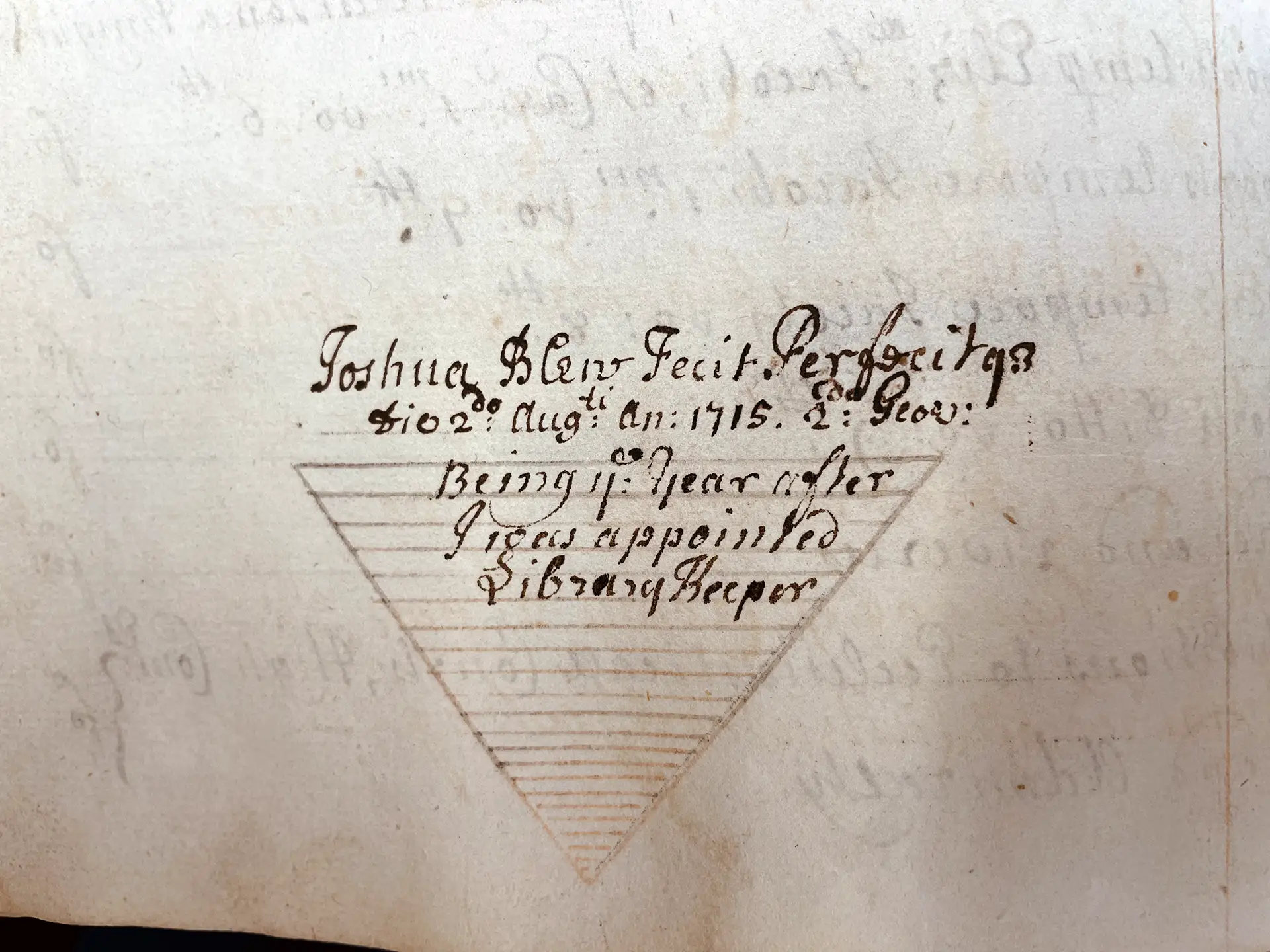

Joshua Blew stepped up to the role of Librarian in 1713. Entering service as the fourth butler in 1709, he became Librarian four years later. Over five decades, he rose to the rank of Chief Butler without ever relinquishing his library duties.

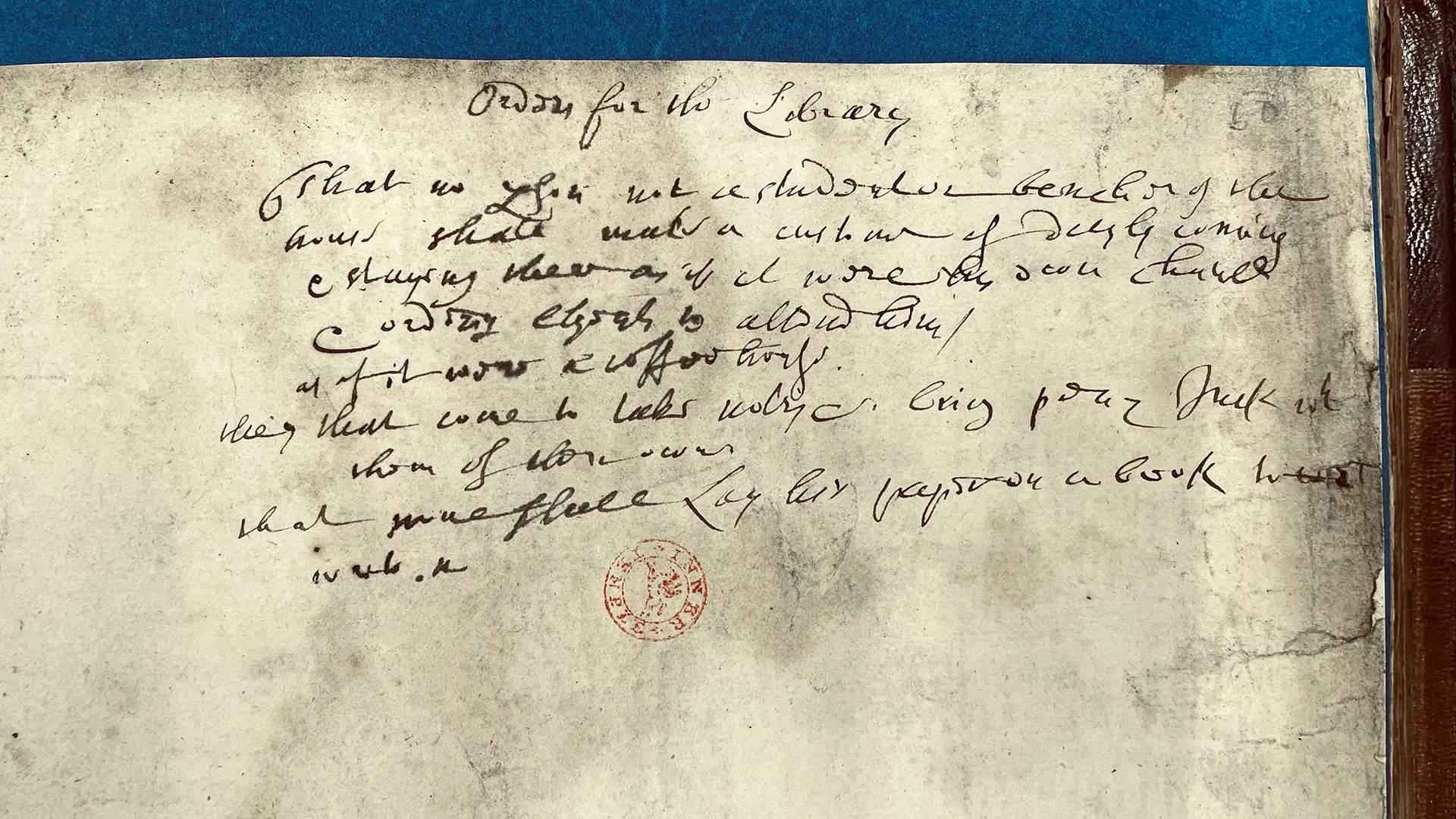

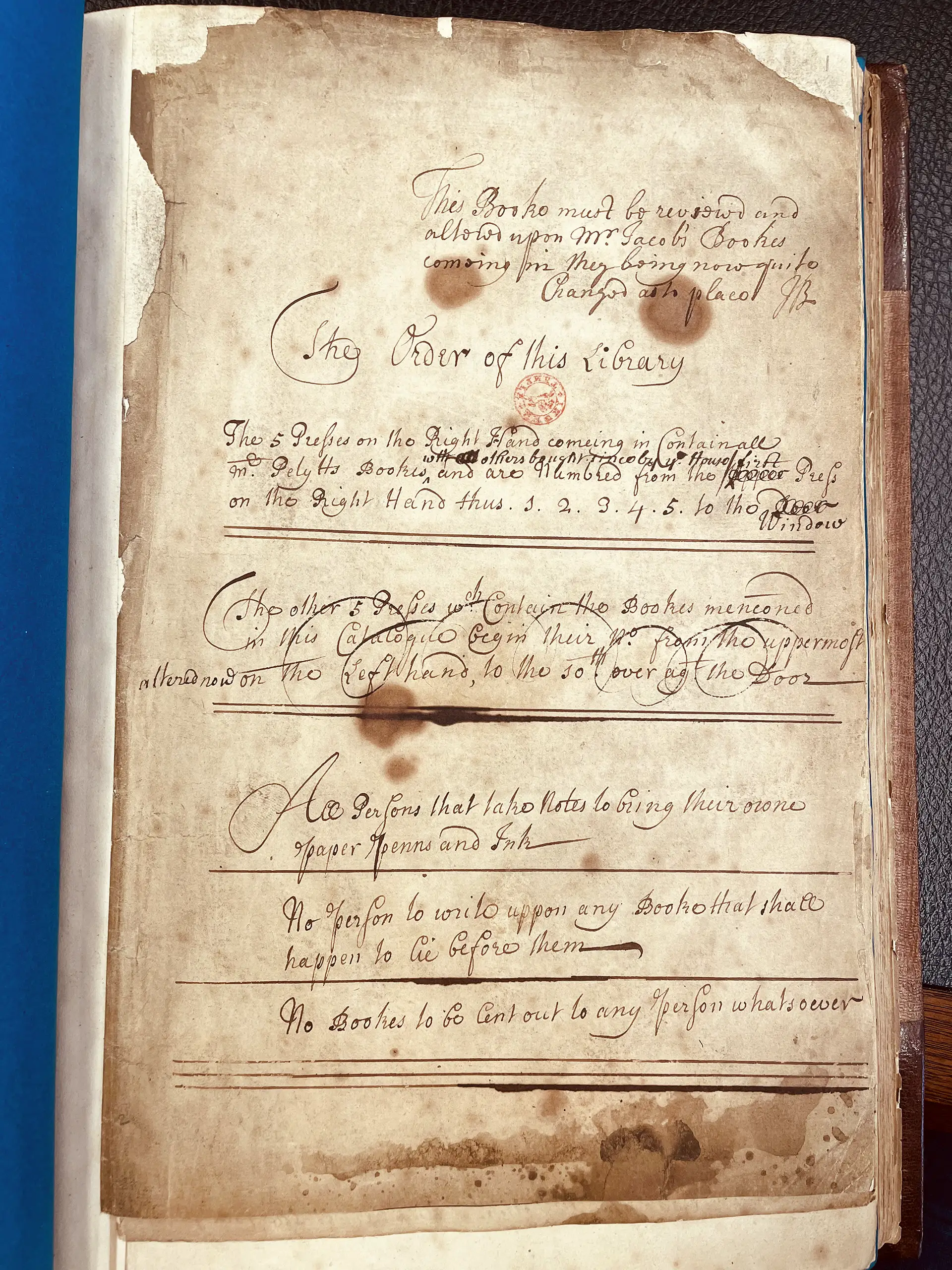

Josuha Blew’s recorded “extraordinary service” to the Inn is far wider ranging that the scant highlights that follow – he indexed and collated the rules and orders of the Inn, oversaw the workmen setting the gates of Hall, inventoried the effects of deceased members and, most importantly, attended the weighing of the meat. Blew revised Carter’s catalogue in 1715. Now entitled The Order of this Library, it established some enduring rules:

- “All persons that take notes to bring their own paper, pens and ink”

- “No person to write upon any book that shall happen to lie before them”

- “No books to be lent out to any person whatsoever”

The subsequent catalogue in 1733 remained in use for four decades.

Blew was also a collector. Ten years after he relocated to 8 Fig Tree Court, the fire of 1737 destroyed both his chambers and his collections. In correspondence he laments both the destruction of his collections, and his wife’s illness which felt was “a result of the great fright at the time of the fire”. A posthumous auction catalogue of his effects shows his diverse interests, for they include such choice items as framed seaweed pictures, Roman artifacts, and a sword he attributed to Edward VI.

The catalogue also lists “12 prints of birds etc. beautifully coloured by [George] Edwards”. Known as the “father of British ornithology”, Edwards published seven volumes containing hand-coloured etchings of birds and non-native mammals. In Gleanings of Natural History Edwards’s illustration for the ‘Gerba’ notes:

- “Mr. Blew, Librarian to the Inner Temple, had also lately one of them living … the stuffed skin of which he lent me to examine.”

This was not the only specimen Blew provided. He resigned in 1763, financially secure in retirement, presumably to enjoy his remaining collections!

In 1763, Charles Chambers, a clerk in the Sub-Treasurer’s office, succeeded Blew. He supplemented the standard £20 salary with tasks such as winding the clocks and keeping the buttery books. He also received a one-off reward of £3 and 19 shillings for “apprehending two persons dropping a child”. Chambers continued Blew’s work of compiling and indexing the Inn’s Acts of Parliament and Bench Table Orders. However, unlike Blew, Chambers appears to have faced financial difficulties due to illness in later life, prompting his widow to petition the Inn for assistance after his death. The Inn granted her a £30 gratuity. Librarian until his death in 1777, he was buried on The Inner Temple side of the Churchyard. The records note “ground given; no fees paid”.

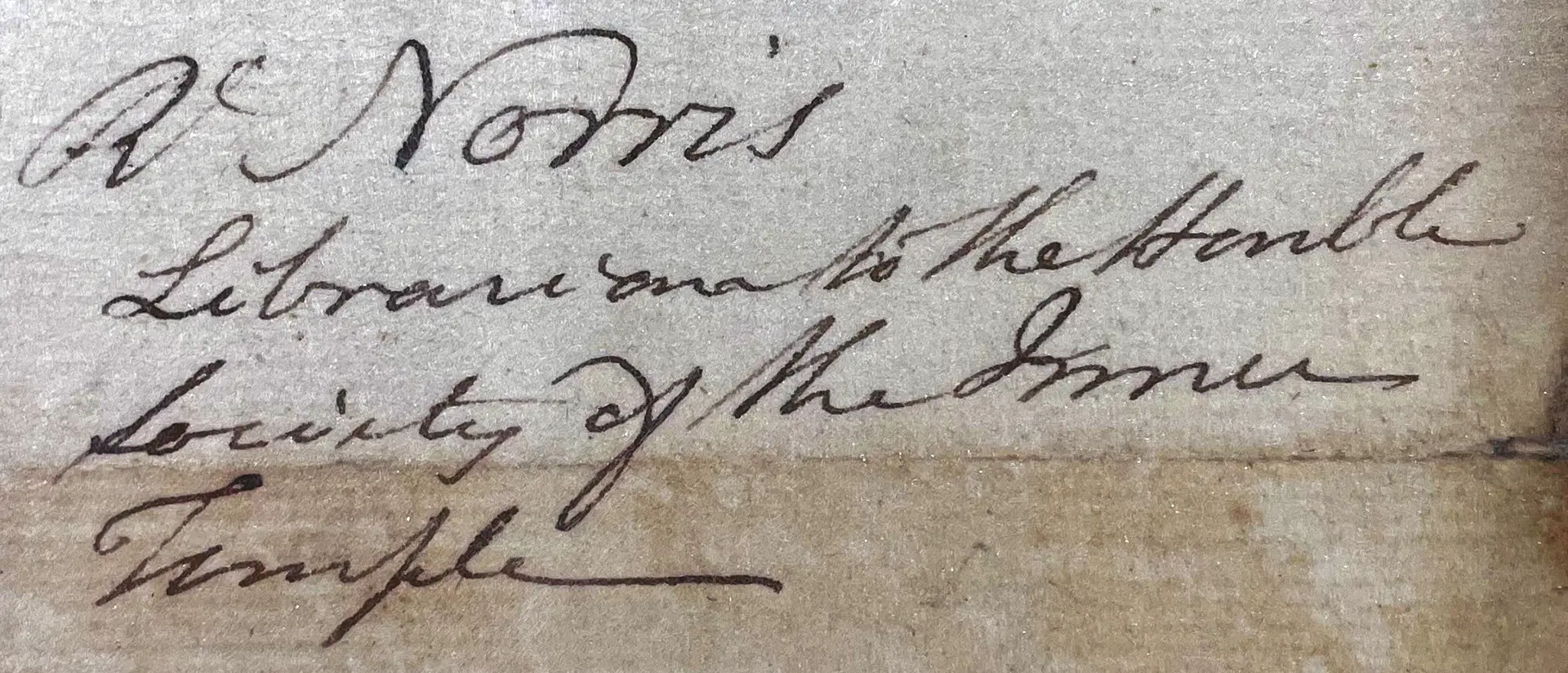

Our next Librarian, the Reverend William Jeffs (who in his capacity as Reader of the Temple Church had baptised Charles Lamb in 1775) was appointed in 1777. He was no stranger to the Library. In 1771, he assisted when Bench Table commissioned work to catalogue the Library’s books and insert an engraved bookplate into each volume. Two copies of the catalogue survive: one draft, and one more elegant and formal. Upon becoming Librarian, Jeffs received the same remuneration as Chambers: a £20 salary and a £10 allowance. He died in post in 1783, and his death prompted Bench Table to question “whether there shall be any Librarian in the future”. Ultimately, they affirmed the necessity of the role, introduced new guidelines for the position, and in 1784 appointed Randall Norris (the salary remained frozen at £20).

By 1801, Norris had become Sub-Treasurer and in 1806, he received £100 back pay for his continued library duties and an extra £20 for preparing the first printed catalogue (a revision of Jeffs’ work). His library credentials were questionable; in 1800, he failed to respond to a Select Committee inquiry about public records, only to deny possessing them despite evidence to the contrary. Charles Lamb wrote to Henry Crabb Robinson, affectionately criticizing Norris’s abilities:

- “In him I have a loss the world cannot make up … To the last he called me Charley. I have none to call me Charley now. Letters he knew nothing of, nor did his reading extend beyond the Gentleman’s Magazine. Yet there was a pride of literature about him from being among books … Can I forget the erudite look with which, when he had been in vain trying to make out a black letter text of Chaucer in the Temple Library, he laid it down and told me that ‘in these old books, Charley, there is sometimes a deal of indifferent spelling’, and seemed to console himself in that reflection.”

That copy of Chaucer from 1602, read by Norris as ‘Charley’ Lamb looked on, is still in the Library collection.

Randall Norris stood down in 1818, and thereafter the operation of the Library changed. Those that follow are all now guided, supported, or controlled (depending on your point of view) by the creation of a new position.

Despite the presence of a librarian, “there were frequent unfavourable comparisons with Lincoln’s Inn”, and on enquiry it was discovered that Lincoln’s Inn had a Master of the Library, so The Inner Temple decided that they must have one too.

Francis Maseres was the Master of the Library that never was. He served as a Bencher for 50 years; he sat on every committee under the sun; he was Treasurer 1781–82. Nonetheless, he attracted disapproval. His correspondence is described as “readable without being exciting; matter of fact and unimaginative”; and he himself as “pedantic” and “lacking in tact and discretion”. But despite that, and with his passion for the Library, he was the obvious first Master of the Library, notwithstanding his having reached the age of 83 in 1818 when the post first became available.

Be that as it may, the Benchers made it clear that they were not having him, and the whole matter was rescinded “after a fortnight of considerable disagreement”. It was not raised again until 1825, Maseres having died in 1824.

The first official Master of the Library was Sir John Gurney. He was a clever lawyer with a practice that now could be described as human rights. He defended in a series of high-profile cases against publishers and activists charged with seditious libel and treason. He married the daughter of William Hawes, a great physician and philanthropist. That makes it all the more curious that he became known as a harsh, though independent, judge, now chiefly remembered as the last judge to sentence to death two men, consenting adults, for homosexual acts in a private room. That was in 1843. The committing magistrate himself pleaded for mercy for them. Charles Dickens wrote the case up. But both hanged and were posthumously pardoned under the Alan Turing Law in 2017.

Before Sir John Gurney became Master of the Library in 1818, the Library was under the guidance of “a tall, well-made figure, with a fine expressive countenance”. Reverend William Henry Rowlatt began his career at the Bar in 1804, but soon shifted to farming. His father suffered financial ruin due to “the criminality of others” in 1812, and by 1814 Rowlatt had taken holy orders. Moving to London, he immediately became The Inner Temple Librarian, and later Reader of Temple Church. He introduced several improvements, including better lighting and cleaning, extended opening hours, and new catalogues. He also secured a pay rise to £100 per annum, rising to £150 by 1838. By 1825, the Library was under strict rules as the Library Committee asserted its authority. Despite a petition in 1829 requesting an end to the rule that books might only be taken down by the Librarian, the rule was still in place in 1833. The Committee had concluded that it was perfectly acceptable and “as per the practice in the British Museum”.

In contrast to a seemingly successful library career, Rowlatt faced bitter disappointment in terms of his advancement in the Church. Despite being presented to the living of St Bride’s by the then Lord Chancellor, his obituary records that he was “prevented from enjoying [it] by a series of transactions literally singular in the history of Church patronage”. Rowlatt’s supporters believed that the living was illegally bestowed upon another preacher, perhaps at the behest of the Bishop of London. His grievances are detailed in his self-published 1835 pamphlet, Church Patronage: the Case of the Rev. W. H. Rowlatt … With Respect to the Living of St. Bride’s.

In 1856, we encounter the seventh and first full-time Librarian, John Edward Martin. Contemporary newspapers paint a picture of the consummate librarian. The Westminster Gazette proclaimed that “His courtesy was proverbial, and his acquaintance with bibliography was by no means exclusively legal in its extent” whilst the Abergavenny Chronicle recorded that “Mr Martin was the refuge of the distressed barrister … few indeed were the legal points, however obscure, on which he could not at once name the works which ought to be consulted”. Books were clearly in his blood; his father was a bibliographer apprenticed to John Hatchard of Piccadilly.

Martin expanded the Library to eight large rooms over 20 years and simultaneously acted as private librarian to the Dukes of Bedford and Northumberland, and the Marquess of Ripon. His starting salary of £250 had risen to £350 by 1860, and £600 by 1880. Performance-related pay, perhaps.

The Westminster Gazette proclaimed that “His courtesy was proverbial, and his acquaintance with bibliography was by no means exclusively legal in its extent.”

Outside of the Inn’s records Mr Martin appears giving corroborative evidence before Commissioner Kerr in the case of an Inner Temple barrister accused of stealing a book from the Library, feloniously receiving the book with a guilty knowledge, and selling it for 10 shillings. The sentence – “imprisoned with hard labour for six months”. Be warned, would-be book thieves.

with Rules, 1715 [Misc. MS no. 4]

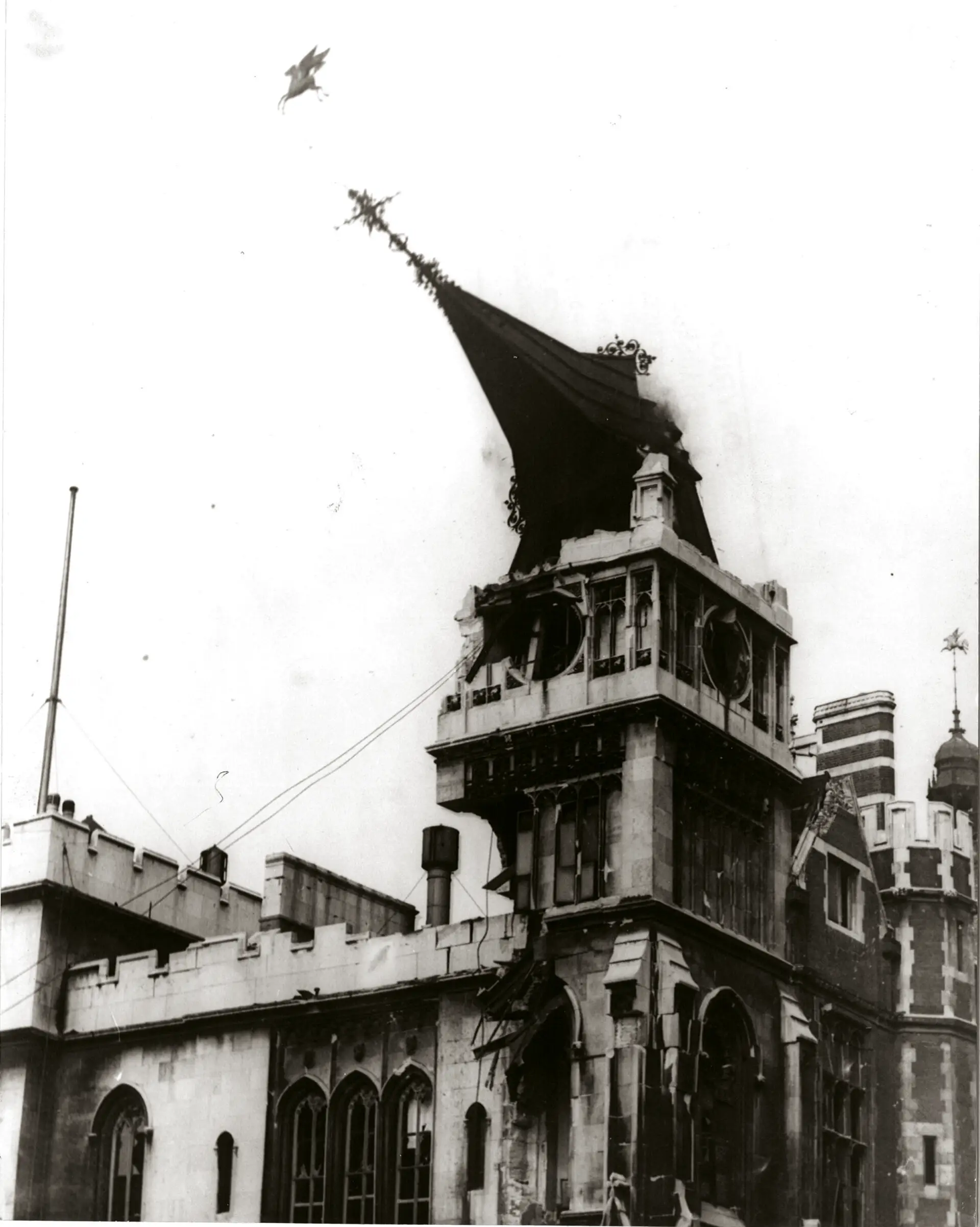

His successor, Frederick James Snell, was Librarian from 1925 to 1939. According to a contemporary, “Snell the Librarian sat at a desk just by the clock tower. He also had a room, where a clutter of old books and MSS were kept, which he used for a nap every day after lunch, for about an hour, and where the staff had tea.” He resigned in 1939, perhaps fortunately so, as the clock tower was destroyed a mere two years later during the war.

Returning to library governance of the same period, between Sir John Gurney in 1825 and the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, there were 120 Masters of the Library. Almost always they became Treasurer the year following their tenure as Master of the Library. They are all reflections of the historical traditional career of the barrister, with a vast predominance of young men from aristocratic and/or clerical families. Most were major public school and Oxbridge educated. Most went on to the Bench, either here or in the colonies. Many were politicians, many distinguished writers – mainly on legal subjects. They were elderly, taking on the joys of the Mastership of the Library and the distinction of being Treasurer as twin peaks of a long career.

But amongst them all there is so much more. We find a close friend of Lord Byron, a Shakespearean scholar, and the nephew of Sarah Siddons. We find the bestselling author of a satirical novel with the snappy title Ten Thousand a Year, as well as three or four first-class cricketers, the man who became England’s first Director of Public Prosecutions in 1880, and the first Jew to graduate from Cambridge. Then there is Sir Harry Poland, who wrote his memoirs wonderfully titled Seventy-Two Years at the Bar, and Lord Darling, described by The Times as of “considerable literary power and no legal eminence”. He gave to the Library one of our greatest treasures – the earliest known depictions of the law courts. And amongst all that privilege, there were also whispers of equality of opportunity.

He gave to the Library one of our greatest treasures – the earliest known depictions of the law courts. And amongst all that privilege, there were also whispers of equality of opportunity.

Sir George Rose was Master of the Library in 1834, and Treasurer in 1835. To put him in context: he is sandwiched between Edmund Henry Lushington (Charterhouse and Queens’ College Cambridge, and Chief Justice of Ceylon) and Henry Bickersteth, 1st Baron Langdale (Caius College Cambridge, and Master of the Rolls). But Rose got to the Bar against all odds. He was born in Tooley Street in Southwark, and his father was a barge owner. Young George got a charity scholarship to Westminster School. He went to Peterhouse Cambridge, until poverty made him leave. Eventually he returned to take an MA at Trinity. He became a serious lawyer, and a famous wit and poet. A lot of his 18th century satirical political wit does not stand the test of time, but this ditty about his two opponents in a case – Mr Leach and Mr Hart – has done so:

- “Mr Leach made a speech, angry neat and wrong; Mr Hart on the other part was right, but dull and long.”

And Rose was not the only one; a far more famous name two years later in 1836, Sir Frederick Pollock was Master of the Library – the first of a long line of very distinguished lawyers, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer, politician, mathematician, Fellow of the Royal Society – but he was born in Charing Cross, the son of a saddler.

In a happy circularity, in 1882, Frederick Pollock’s son Charles Pollock also became Master of the Library, following in his father’s footsteps.

The pattern of annual Mastership changed in the Interwar period with the appointment of Charles Le Quesne in 1935. He occupied the post until he died in 1955.

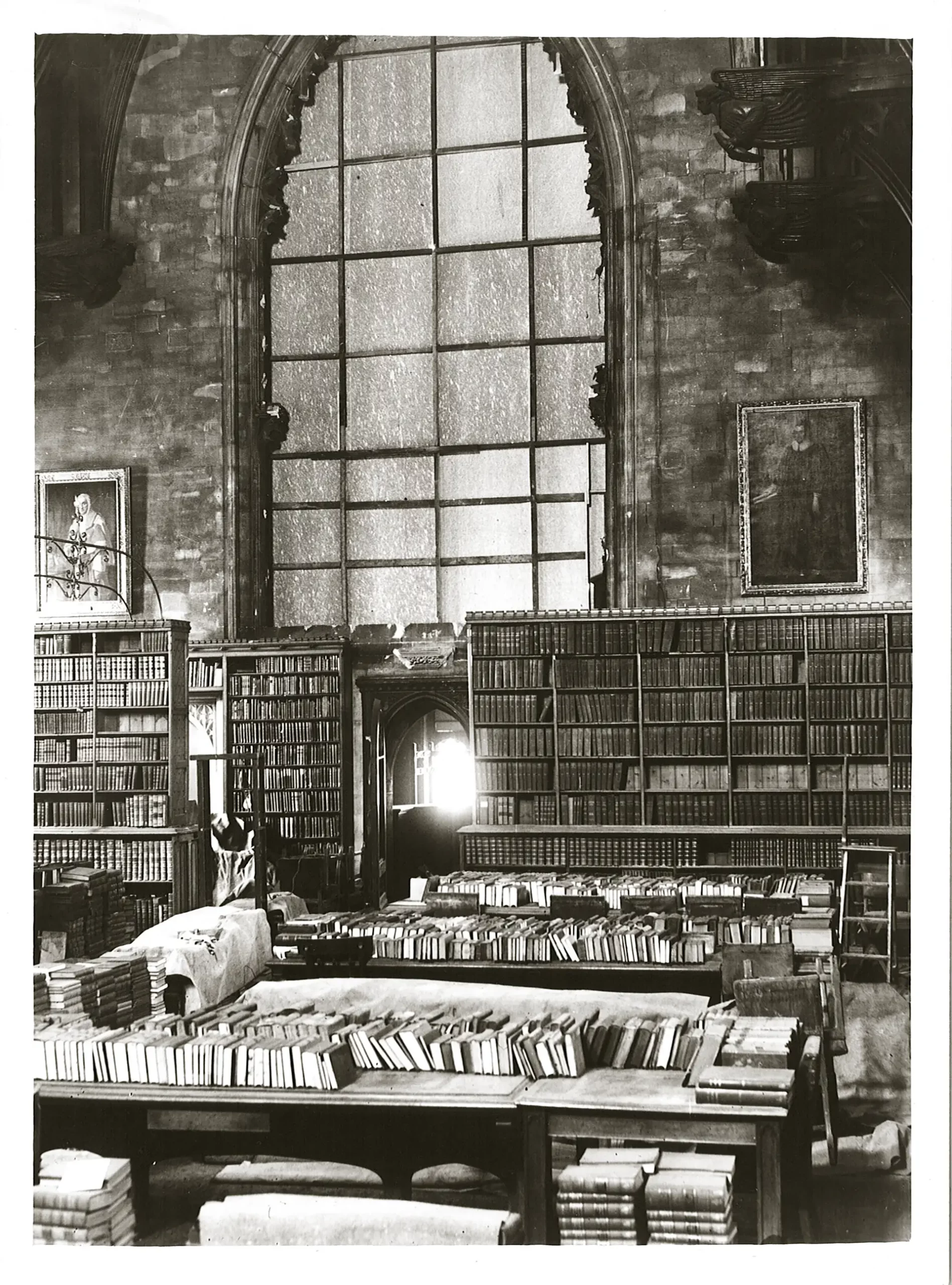

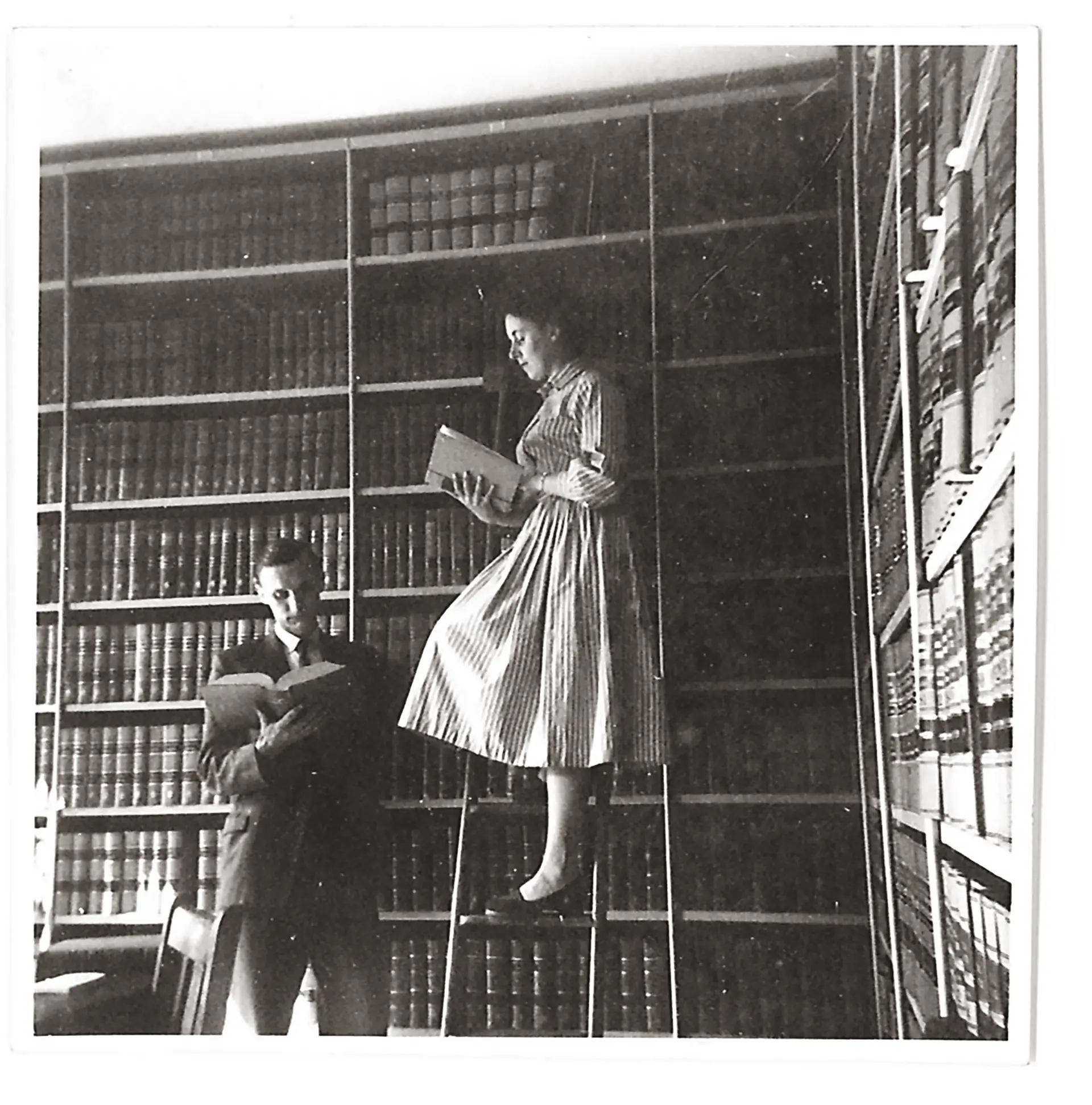

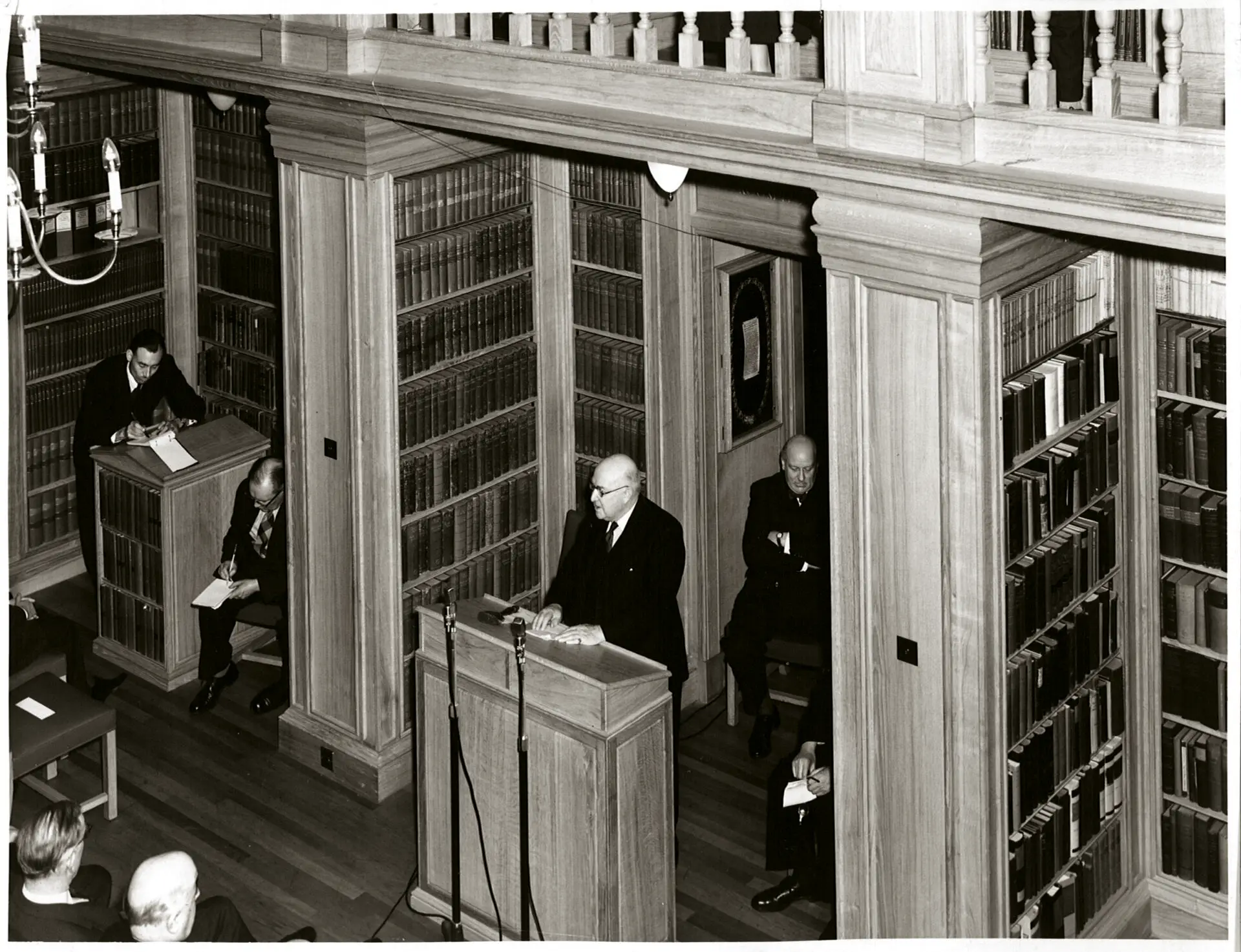

The difficult task of running the Library during wartime fell to Eric Albert Powell Hart. He was responsible for the evacuation of our manuscripts in the early part of the war, and suffered the appalling horror of the incendiary device that destroyed the Library in 1941. Contemporary reports record that more damage was done by water than fire, and that the foul weather resulted in many volumes being frozen to the shelves. The reports also record the deployment of library staff in non-traditional library duties such as shovelling ashes and removing lead and girders – all with the “rain, snow, and ice” adding to the difficulty. Despite all of this, Mr Hart was still at the helm when the new Library rose from the ashes in 1958. Hart worked his way up the ranks from Assistant Sub-Librarian in 1925, to Sub-Librarian in 1931, then Librarian in 1939. Retiring in 1964, he overlapped for some years with his successor, Wallace Breem, who was promoted to the role as Librarian and Keeper of Manuscripts in 1965.

Breem’s legacy to the Library includes widespread handwritten notes, comments and annotations in books, lists of staff duties and detailed reports. A founding member of the British and Irish Association of Law Librarians – BIALL, as it is known – is still going strong and Mr Breem is remembered through a memorial award in his honour, sponsored by both the Inn and BIALL. Whilst undoubtedly a busy librarian, he is also remembered as a distinguished author of three historical novels. Arguably the most well-known, The Eagle in the Snow, features a certain General Maximus, and was the inspiration for some key scenes in Ridley Scott’s blockbuster film Gladiator.

There is a delightful small world symmetry in the fact that in 2012 the BIALL Wallace Breem Award was bestowed on the staff of The Inner Temple Library for their “considerable contribution to the legal information profession”, under the guidance of Breem’s successor, and Librarian number 12, Margaret Clay. Margaret modernised the Library with digital advancements: automating the catalogue, introducing online databases, launching the website in 1998, developing the AccessToLaw site, and introducing the ‘Current Awareness’ blog. Launched in 2007, it now reaches nearly 10,000 subscribers every day.

Margaret and the team packed up the Library when it closed for Project Pegasus in 2019, and when it reopened in its current reconfigured form in 2022, it was under new management. Rob Hodgson became 13th Librarian of The Inner Temple, mid-pandemic, in November 2020, and felt that being number 13 might be unlucky for some. In the interest of ‘making your own luck’ he posits a minor revision to the accepted chronology: for a brief three-month window in 1777, John Spinks took over the duties of Librarian until Reverend Jeffs formally took up his post. With a minor stretch of credulity, that makes Rob the 14th Librarian. A luckier number, perhaps.

Samuel Carter, the Inn’s first recorded Librarian, set out his rules, declaring:

- “That no person not a student or Bencher of the House shall make custom of daily coming and staying there as if it were his own chambers and ordering clients to attend him as if it were a coffee house.”

What would he make of the Library today, with its sofas, bookable space, phone booth, and the coffee cups on every desk?

We briefly round off some of the more recent Masters of the Library. Masters Sedley, Sumption, Beatson, and Sharpe, all are exceptionally distinguished – variously judges, writers, and academics. Master Sharpe was the first woman to become Master of the Library.

Then I’m afraid [says Master Sally Smith] there is me. Someone analysing the Masters of the Library in 100 years’ time will say “we do not know much about her” and pass on with a sigh of relief to today, when Master James Dingemans has taken over the role.

And so, it goes on, we hope through another few centuries.

For the full video recording:

innertemple.org.uk/librarysnapshotsy

Sally Smith KC

1 Crown Office Row

Robert Hodgson

Librarian and Keeper of Manuscripts