Human Rights in Britain and France

from Thomas Becket to the French Revolution

From a lecture for The Inner Temple History Society held on 10 October 2022 (abridged by the author)

English and French lawyers and philosophers have influenced each other since they shared a francophone culture for some 300 years after the Norman Conquest. The recognition of the right not to be enslaved illustrates this co-operation between the two countries who, despite this, spent much of the last millennium at war with one another.

In most parts of the world, until the 19th century, enslavement was generally legal in the sense that it was in accordance with contemporary national laws, whether customary laws, or the enactments of legislatures. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, in parts of Northwest Europe, slavery was replaced, first by less oppressive forms of unfree labour, and then by consensual arrangements. In France and England, after the 12th century, the status or institution of slavery permanently ceased to be recognised by law. It is sometimes said that slavery was then delegalised. This did not happen outside Northwest Europe until the 19th century.

In France and England, after the 12th century, the status or institution of slavery permanently ceased to be recognised by law. It is sometimes said that slavery was then delegalised. This did not happen outside Northwest Europe until the 19th century.

The words slavery and enslaved are used in different senses. The primary meaning refers to one person exercising the powers of ownership over another as if the other were a chattel (chattel slavery). This form of slavery was usually permanent. It is inherited through the mother, unlike other types of status, which are inherited through the father. It is the only inherited form of slavery. A second meaning is a criminal convicted of an offence by a competent court and sentenced to work (penal slavery or servitude). This may be for a fixed period, or for life. A third meaning is where a prisoner of war is forced to work and cannot be permanent. Fourth and fifth meanings are where a person agrees to serve without pay, either for a fixed period (an indentured servant and exploited children) or for life (debt bondage and forced marriage). A sixth meaning refers to cases where a person enjoys the right of personal liberty but does not have the right to vote or otherwise participate in the making of the laws that govern him (political slavery). This is typically where the government of a country is a despot or a colonial power or where women are excluded from public life. In all these cases the forced labour is in accordance with the law of the place where the parties are situated. There are also forms of illegal slavery, where one person holds another under their control by force (‘modern slavery’ and people trafficking). In the 15th to 18th or 19th centuries, European settlers practised chattel slavery in their Caribbean and American colonies mainly by transporting across the Atlantic millions of enslaved people purchased from their captors in West Africa.

Chattel slavery was abolished by law in the British Empire in 1833, in French colonies in 1848, and in the USA in 1865. The Geneva Convention to Suppress the Slave Trade and Slavery of 25 September 1926 made chattel slavery unlawful under international law. Other forms of compulsory work are permitted by international law, such as the European Convention on Human Rights 1950, article 4. In England, penal servitude was introduced as a substitute for the death penalty by an Act of 1857 which remained in force until 1948. Debt bondage became unlawful under international law by the Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery of 30 April 1956 and other treaties. International humanitarian law (the Geneva Conventions) also permits prisoners of war to be forced to work.

Many enslaved people have been men engaged in heavy work in unsafe conditions, such as in the mines of ancient Greece and Rome, and the plantations of the Americas in the 16th to 19th centuries. But most were required to provide domestic, including sexual, services, and these people were, and still are, mainly women and girls.

Uniquely oppressive features of chattel slavery are that it is hereditary and that the enslaved person is permanently separated from their homeland, family, and social network.

The Domesday Book, prepared in 1066–1087, reveals that enslaved people constituted at least 20 per cent of the overall population of England in 1066. It was during the reigns of the French-speaking Plantagenet and Angevin kings, that slavery disappeared. From the 11th century, in wars fought in France and in England, victorious armies did not enslave those whom they defeated. Nor did they raid each other for slaves, nor enslave debtors who could not pay their debts.

The Domesday Book, prepared in 1066–1087, reveals that enslaved people constituted at least 20 per cent of the overall population of England in 1066. It was during the reigns of the French-speaking Plantagenet and Angevin kings, that slavery disappeared.

It is impossible to know all the reasons why legal chattel slavery disappeared from France and England about the 11th to 12th centuries and was not re-introduced when it was allowed in their colonies. In this article we are considering only the arguments against slavery advanced by lawyers and philosophers up to the end of the 18th century. Amongst ancient Romans and early Christians there was no movement for abolition, but there were writers such as Seneca and St Paul who taught that all people were equal, whether enslaved or free, and that enslaved people should all be well treated.

John of Salisbury (c1116–1180) was born in England and educated in Paris, then the most important centre of learning North of the Alps. John dedicated his Policraticus (1159) to Becket. It is the first complete work on political theory written in the Middle Ages. It foreshadows some of the ideas expressed 55 years later in Magna Carta 1215, including the principle that the king must govern for the common good, and according to law (the rule of law). John of Salisbury’s work was still being read 400 years later when it became one of the first works to be printed following the importation into Europe of the art of printing.

John of Salisbury deduced from what he believed to be the descent of all people from Adam and Eve, that everyone should be judged equally on their personal virtues and vices not their status. Addressing slaveholders, John wrote:

“… the whole race of men upon the earth arose from the same origin… They are slaves, it is said: nay they are men … remember that fortune has equal power over you. You may yet see him a free man; he may see you a slave… Let your slaves cherish rather than fear you… for what is cherished is loved, nor can love be mingled with fear…”

John’s ideas are illustrated in stained glass windows and sculptures in churches where Adam and Eve are portrayed as equals, both of them working, she spinning and he digging. Examples are at the Cathedrals in Chartres, where John became Bishop after Becket’s murder, and Lincoln.

French was the language spoken by nobles’ government in England well into the 13th century. Henry II (reigned 1154–1189) introduced the common law. Most of its vocabulary is of French origin, including: action, bail, contract, court, defence, jail, judge, jury, nuisance, sentence, tort, verdict and many others. By that time, there were unfree men known as villeins and serfs, but no slaves. So, there was never a time since then at which there was a legal means for one person in England to treat another as a chattel. In 1215 Magna Carta, article 39, did not protect people of unfree status. It includes (in translation from the Latin): “No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned … but by the lawful judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land.” The Latin and French words homo and homme both included women. The statute Liberty of the Subject 1354 is still in force. In the English translation from the original French, it applies to people of any status: “No Man (homme) of what Estate or Condition that he be …”

In 1315, King Louis X of France (1314–1316) issued a decree enabling French serfs on certain Crown lands to purchase their freedom. The decree started with the words “Since, according to the law of nature, each person is born free…” This is an echo of Roman law that foreshadowed the American and French declarations of rights of the late 18th century.

The 14th century chroniclers described the Peasants’ Revolt in England in 1381. One of the demands of the peasants was for social equality and the end of serfdom, summarised in the ditty: “when Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?” Since the Bible does not refer to Eve spinning, this seems to be a reference to the images of Eve spinning and Adam digging that appear in the earlier stained glass and other works of art.

The disappearance of legal slavery in France gave rise to conflicts of laws. The Southern neighbours of France included Muslim ruled territories of Spain and North Africa that recognized chattel slavery. Enslaved persons continued to arrive in France from them. Some came seeking refuge from these neighbouring countries, while others were brought to France by those claiming to be their ‘masters’. In 1402, four such refugees were freed by the Court in Toulouse. The court declared that it was a privilege of Toulouse that “all slaves became free as soon as they set foot in the town”. This is known as the ‘free soil’ principle.

French and English law both adopted the maxim of Roman law favor libertatis (the law favours liberty). This principle was introduced into the English common law from canon law (law of the Church) by judges who had trained in the Church’s theological faculties. In about 1470, Sir John Fortescue, a former Chief Justice of England, wrote:

“A law is also necessarily adjudged cruel, if it increases servitude and diminishes freedom, for which human nature craves. For servitude was introduced by man for vicious purposes. But freedom was instilled into human nature by God. Hence freedom taken away from man always desires to return, as is always the case when natural liberty is denied. So he who does not favour liberty is to be deemed impious and cruel. In considering these matters the laws of England favour liberty in every case.”

By the time Fortescue was writing, it might have been thought that slavery would never again be practised by French or English people. But that was not what happened. Instead, Europeans took over a trade in enslaved Africans that had long existed. Both before and after the 15th century, African and Arab traders transported enslaved Africans from sub-Saharan Africa to the slave markets of the Middle East, sometimes overland, sometimes by sea.

In 1444, Portuguese traders transported enslaved Africans by sea from South of the Sahara to Portugal for the first time. The voyages to America of Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci followed. An account attributed to Vespucci described how he enslaved indigenous people and sold them in Cadiz in 1498.

In the first decade of the 16th century, Europeans imported slaves into Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic and Haiti), first from neighbouring Caribbean islands, and then from Africa. About the same time as these developments, in 1516, Thomas More published his fictional description of the island he called Utopia, in which everyone is equal. By that time, there were no legally recognised unfree people in England. More was responding to the accounts of the voyages of Vespucci published in 1505. He may also have been influenced by John of Salisbury, whose Policraticus was printed in 1513.

More wrote Utopia in Latin. In it, he identifies three categories of people as servi (the plural of the Latin word servus) that is often translated as ‘slave’. But it may also mean a servant, a serf, or a free serving man. More did not include chattel slavery in Utopia. He defined those servi who were forced to work as convicts and prisoners of war. He also uses the word servi for people we would call economic migrants who entered the country with a work permit.

In the 16th century, in the Southwest of France, enslaved people continued to arrive in small numbers from Spain and North Africa. In 1558, there was a decision of the Parlement, or High Court, of Toulouse, in which the court stated that a slave becomes free as soon as he sets foot in France. The principle became a maxim of French law. In 1571, the Parlement of Guyenne, sitting in Bordeaux, made an order which released from slavery some North Africans who had been brought to France. The reason given by the court was that “France, the mother of liberty, does not allow that there be slaves”.

From 1571 onwards, the French courts consistently ruled in favour of enslaved Africans seeking their freedom. Such cases were more frequent in the late 17th century when Europeans were transporting increasing numbers of Africans to the colonies and bringing some of them back across the Atlantic on visits to France.

Jean Bodin (c1530–1596), was a French lawyer and politician, and the author of one of the major 16th century works on political thought, The Six Books of the Republic, first published in 1576. Bodin made references to Utopia in which More includes both strong criticism of the harshness to the poor of contemporary English law and a description of a fictional state about the size of England with a democratic and republican constitution. Bodin recounted decisions of the Parlement of Paris, and the 1558 decision of the Parlement of Toulouse. The book was widely read in England. A 1606 English version translates Bodin’s words as “the slaves of strangers so soone as they set foot within France become franke and free”. Bodin refuted the argument that a prisoner of war could with justice be made a slave: those who lost a war might do so because they were weak, not because their cause was unjust. He attacked the cruelties to which slaves had been made subject. In France, if formerly enslaved persons made a contract by which they purported to restrict their liberty to a greater extent than was normal for free people the courts would declare the contract void.

In the 17th century, when French and English settlers introduced chattel slavery into their Caribbean colonies, the French law, known as the Code noir, enacted in France defined enslaved people as chattels (meubles) but gave them some protection against exploitation and abuse. But it was so clearly in conflict with the principles of liberty applicable in France that the Paris Parlement refused to register it. The English colonies enacted their own laws permitting slavery, giving enslaved people less, if any, protection from abuse.

The inconsistency between the colonial laws and the laws applied in France and England led to conflicts of laws. In a 1705 case, Sir John Holt, Chief Justice of England, declared that “as soon as a negro comes into England, he becomes free”. There was no precedent or authority for this statement, and no enslaved people were freed by an English court until 1772. It seems likely that he was inspired by Bodin’s statement about France. English judges at that time looked to French law much as today their successors look to the laws of other English-speaking countries.

By contrast, between 1730 and November 1790, when the Admiralty Court of France was abolished, that court freed 247 enslaved people who had been brought from abroad to France. Of these, 98 were freed before 1770. In 1738, an enslaved African Jean Boucaux sued his ‘master’, Verdelin, who had brought him into France. The French equivalent of an Attorney General argued that all men were born free and equal, that Christianity and the king, and the judges acting in the name of the king, ensured that liberty reigned in France, and that as soon as a slave set foot in France, he gained his liberty. The case decided in 1558 in Toulouse established a maxim of French law. In 1749, Montesquieu argued that slavery could not be a merciful alternative to killing defeated enemies as the Romans claimed: a Christian society accorded higher respect for human life.

In 1765, Blackstone controversially repeated the words used by Sir John Holt, saying they were English law, but citing no authority. This statement encouraged abolitionists to support the application for habeas corpus brought by James Somerset who had been enslaved in the New World, brought to England, and was being held by Charles Stewart in a ship awaiting return to the Caribbean. Francis Hargrave, junior counsel for Somerset, prepared a long argument which he presented to the court and published as a pamphlet. He cited Bodin and the French case law. After much hesitation, Lord Mansfield held that absent statutory authority or any precedent in the common law, the status of a slave under colonial laws could not be recognised in England. Somerset was free, so long as he remained in England. In 1778, the Scottish case of Knight v Wedderburn reached a similar outcome, again after hearing French law.

In 1770, the Abbé Raynal published in both French and English a strong criticism of European colonialism. The chapter on slavery captures his thesis in the short title of the French version “Slavery is repugnant to humanity, to reason and to justice”. In support of abolition, he invoked human rights, and repeated the arguments of John of Salisbury. “All men are brethren, they have one common father, an immortal soul, a future state of felicity …” He warned that Africans in the colonies would rebel, as they did in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1791.

In 1770, the Abbé Raynal published in both French and English a strong criticism of European colonialism. The chapter on slavery captures his thesis in the short title of the French version “Slavery is repugnant to humanity, to reason and to justice”. In support of abolition, he invoked human rights, and repeated the arguments of John of Salisbury. “All men are brethren, they have one common father, an immortal soul, a future state of felicity …” He warned that Africans in the colonies would rebel, as they did in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1791.

Inspired by English abolitionists, a French campaign for abolition commenced in 1782. Prominent supporters included political figures who were to be leaders in the French Revolution: J-P Brissot de Warville, the Marquis de Condorcet and the playwright Olympe de Gouges. Brissot and Condorcet cited from More’s Utopia in a translation published in 1780 that emphasized More’s advocacy of democracy and republicanism. These abolitionists argued that in defining slavery to include only convicts and prisoners of war, and excluding chattel slaves, More was attacking chattel slavery introduced into the colonies.

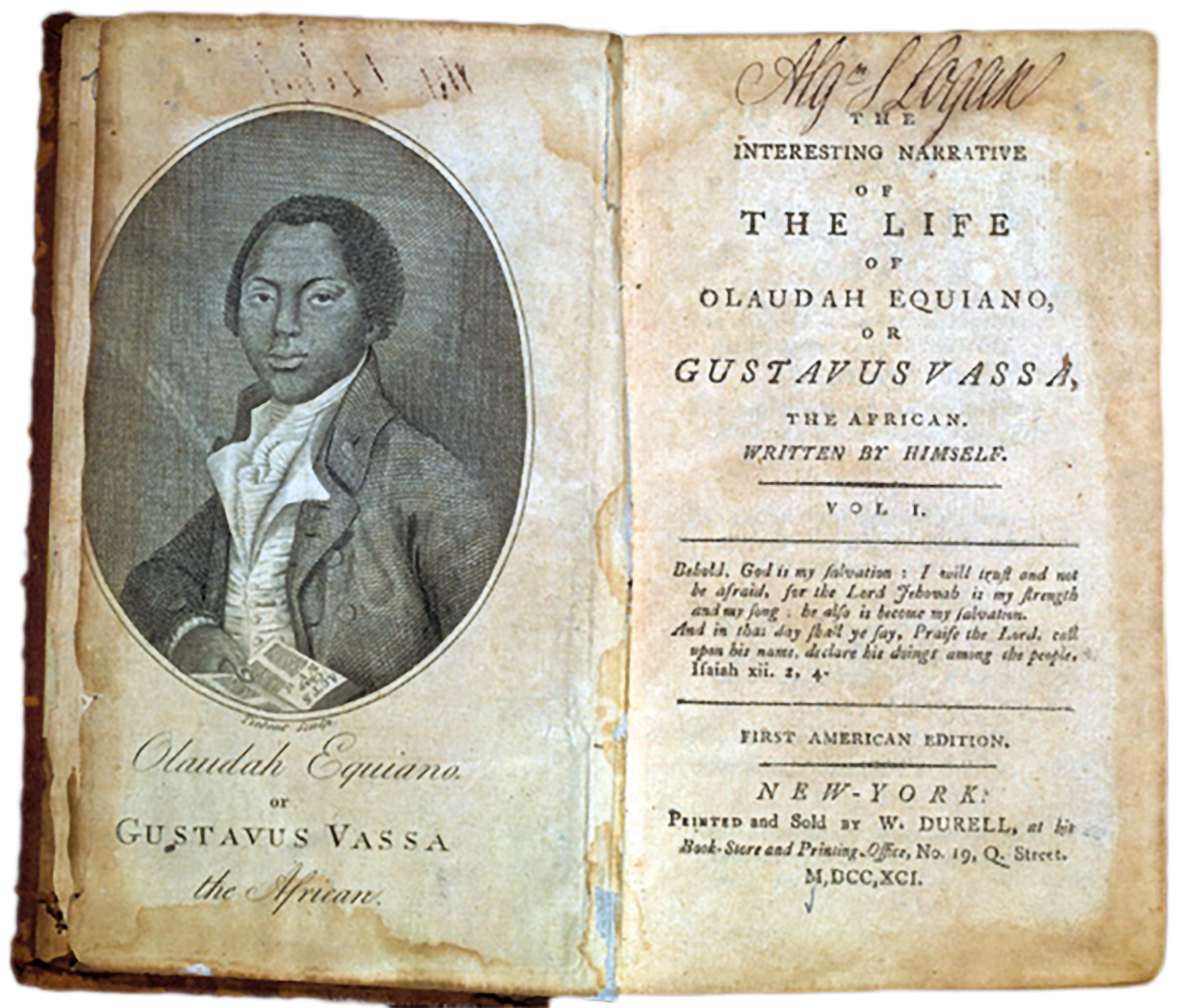

The abolitionist campaign was supported by formerly enslaved people from America invited to England to give lectures. In 1789, Olaudah Equiano (c1745–1797) published a book about his experience, arguing that it corrupted the slaveholders as much as the enslaved, and that it infringed human rights (his own words). This was one of the earliest texts using human rights in its modern sense.

Why does this history matter today?

First, it matters to everyone. The 1833 Act abolishing legal chattel slavery in the British colonies is marked by memorials, such as the one in Victoria Tower Gardens next to the Houses of Parliament. The disappearance of slavery within England itself in the two centuries following 1066 is less well known. To the best of my knowledge, there are no memorials to it.

© Library Company of Philadelphia via Wikimedia Commons

But that disappearance of legal slavery in France and Britain in the 12th to 13th centuries was a momentous event in the history of the world. It was no less significant than the abolition of slavery which occurred in the 19th century. It, too, deserves to be remembered.

One reason why the disappearance of chattel slavery in Europe from the 12th century was so important was because it gave rise to the inconsistency between its illegitimacy in England and France, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, its legitimacy in their colonies and the rest of the world. This inconsistency was a major reason why legal slavery ultimately did not survive all around the world.

This history also matters to lawyers. The disappearance of legal slavery in France and England, and the corresponding recognition of the right to equality, was justified by arguments which had been advanced since the 12th century. In the following centuries, most notably in the late 18th century, lawyers and campaigners in Britain and France continued to influence each other in advancing abolitionist arguments. The anti-slavery statements by Holt CJ and by Blackstone, which became famous in England, and the landmark decisions Somerset’s case in England and Knight v Wedderburn in Scotland, followed the citation in British courts of French case law dating from the 15th and 16th centuries. In modern times, leading human rights texts, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the European Convention on Human Rights, are in large measure the fruit of a dialogue between French and British lawyers. Today, British lawyers and judges commonly take into account jurisprudence from international human rights courts, and from the national courts of other English-speaking countries, but rarely from our European neighbours. Before the 19th century there was no Australian or Canadian case law. Our lawyers and judges looked to the case-law of European national courts, mainly from France. Was there ever more important case law cited in British courts than the French law on slavery, as explained by Jean Bodin, which inspired Holt CJ in 1705 and was cited by Francis Hargrave in 1772?

For the full video recording: innertemple.org.uk/becketrevolution

–

Sir Michael Tugendhat

Master of the Bench